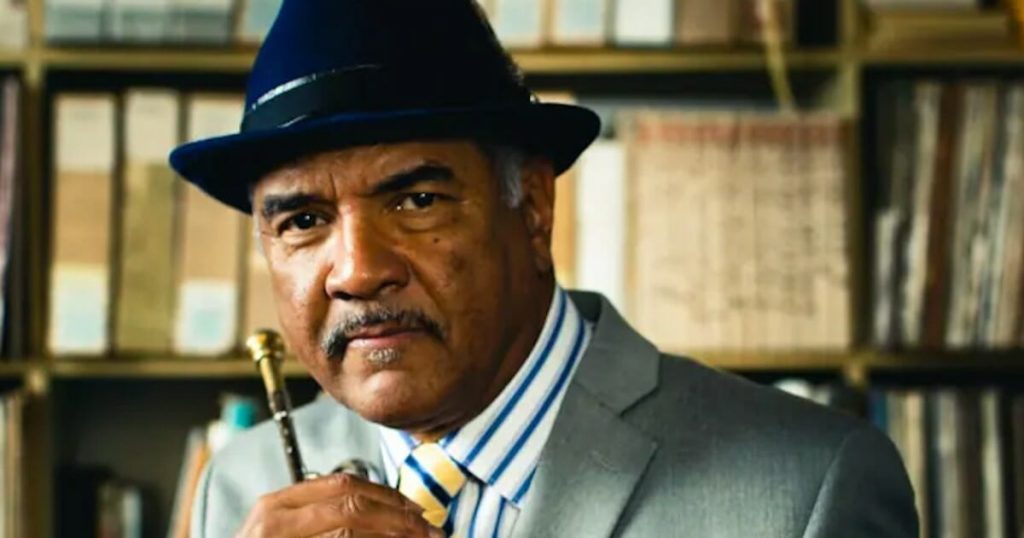

photo: Camille Lenain

***

In early June Wendell Brunious was named the first-ever musical director of Preservation Hall. The 68-year-old trumpeter and vocalist has a long history with the revered institution, having first performed at the Hall at age 23, then becoming its youngest bandleader five years later.

The Crescent City native has toured the globe with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band, recorded seven albums of his own, and appeared with artists such as Wynton Marsalis, The Dirty Dozen Brass Band, Lionel Hampton and Gladys Knight & the Pips. He is also a college educator, who taught music for many years at the University of New Orleans.

Brunious grew up in the 7th Ward amidst a family of musicians and took up the trumpet at age 11. He observes, “My daddy went to Juilliard and was a great trumpet player, as was my brother. My mother was Lester and Burnell Santiago’s sister. I grew up around Willie Humphrey, Percy Humphrey, Kid Thomas and all those guys. The Young Tuxedo Brass Band recorded an album in our backyard called Jazz Begins. The album folds in half and there’s a picture that Lee Friedlander took of my sister and I holding hands and watching the band while my dad’s on trumpet. It’s such an honor to be in this family, but you’ve still got to do your own practicing and your own thinking. It’s not like you’re born with a crown. You still have to earn that crown.”

Given your background, did you always think you’d become a professional musician?

I didn’t know what I planned on being, but I had been exposed to music my entire life. There’s a cut on my daddy’s record [Chief John Brunious’ Mahagony Hall Stompers’ Bye and Bye] that I sang when I was nine years old. You can hear it on YouTube.

I went to business school, and I made good grades. Then when I graduated, I worked at Sears. During my second week working there, the drummer Herlin Riley came in while I was a little manager in the sporting goods department and asked if I still played trumpet.

I told him I did, and he said, “Man, I’m on a gig on Bourbon Street. Why don’t you come over and let the guy hear you because both the drummer and the trumpet player are leaving.” This was at the 500 Club for a burlesque show. I went over there that night and the guy liked the way I played, so he was like, “Can you start on Monday?” That’s where my heart was so I quit Sears. I never went back.

How did you initially come to play at Preservation Hall?

I was playing on Bourbon Street, and I had parked across the street from Preservation Hall. As I was walking back to my car, I decided to look in. I noticed that they didn’t have a trumpet player, so I asked if I could go up there and play. The drummer, whose name was Alonzo Stewart, said, “No, we don’t let people sit in here, man.” Well, I guess I was a little bit cocky, so I took my trumpet out of the case, went up there and started playing. Then after the second song, the doors to Preservation Hall opened, and it was [Pres Hall founder] Allan Jaffe and Kid Thomas. It turns out they did have a trumpet player, but Kid Thomas was in the back having a sandwich so he was a little late getting back to the bandstand. [Laughs.]

Jaffe heard me and he said, “I didn’t know you played music like that.” I told him, “Of course, I’ve been hearing that all my life.” So he invited me to come in and sit next to Percy Humphrey one week, then Kid Thomas the next week and so on. That’s when I became more associated with the Hall and chilled out on Bourbon Street a bit.

Being around those older trumpet players prepared me to be an older trumpet player, like I am now.

What led you to teach at the University of New Orleans?

Ellis Marsalis was the chairman of the music department, and he called one day and asked me to come teach a class. I told him I had been a business major. He said, “No, we’ve got the book. Come teach these kids what and how to play. They’ve got to learn the blues. They’ve got to learn form. They’ve got to learn II-V-I. They’ve got to learn the bass drum.”

So I taught all of these things that I thought were valuable for young musicians rather than being a specialist. They’ve got a lot of specialists in the world now—this guy plays the high notes, this guy plays the low notes and this guy plays the middle notes. I told these musicians: “We’ve got a lot of specialists and God bless them, but you better round out a few of those edges if you’re going to have a career.” I also told them to keep in mind: “They’ve got guys who can out-note you in every symphony in the world. So finding the notes is great, but I want people to feel what you’re doing so that when they walk out, they’re humming and bip-bopping to what they just saw.”

What was your initial reaction upon hearing the offer to become the Preservation Hall musical director?

It was quite a nice surprise. It’s a tender position to be in because you’ve got to know the music, you’ve got to know who can play the music, and you’ve got to know how you can help them improve the music.

I take it seriously because I take the music seriously. It’s bigger than all of us. The music of New Orleans encompasses so many things. It’s Buddy Bolden, King Oliver, Louis Armstrong and Sidney Bechet, but also Fats Domino, Louis Prima, Smiley Lewis and all kinds of people. That’s what makes the New Orleans thing so unique—we’ve got all these things going on at one time, but going in the same direction.

The common denominator is the feeling of the music. It’s supposed to make you move. If you see a New Orleans concert, and I don’t care what kind of music it is—brass-band music, rock-and-roll, rhythm and blues, traditional jazz—if you’re not moving, you’re not hearing the music.