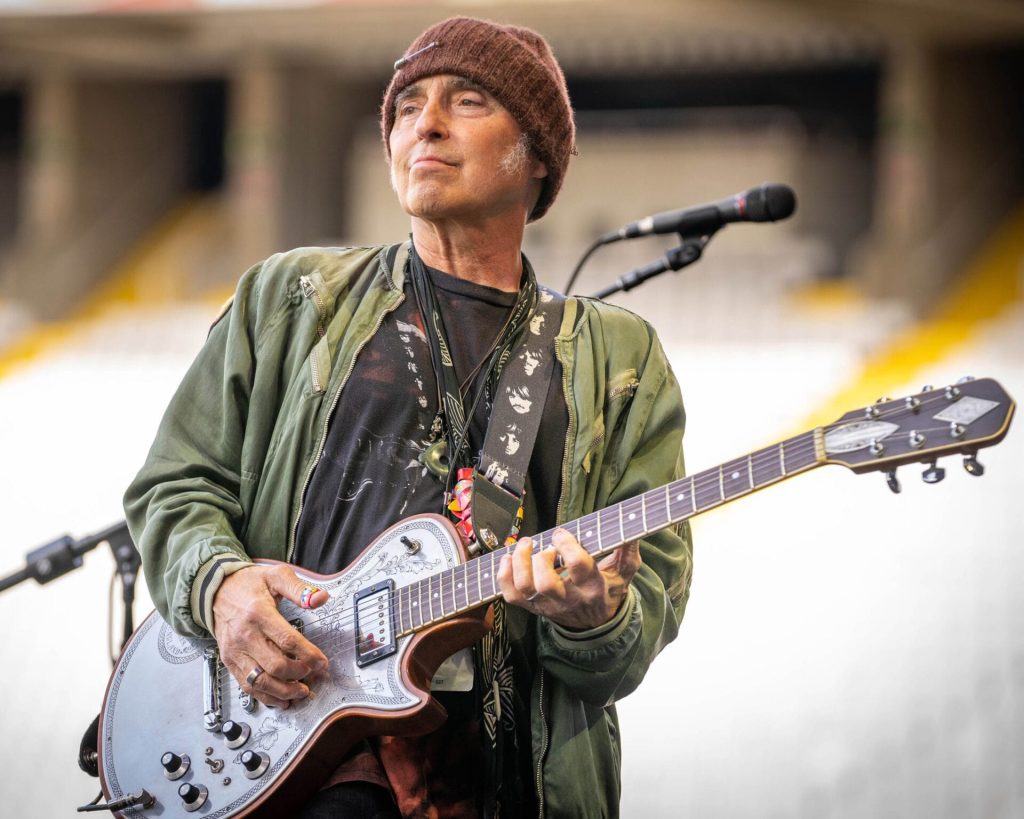

photo: Rob DeMartin

***

“I’ve been blessed with a lot of beautiful moments,” Nils Lofgren attests. “At 18 years of age, while I was living at David Briggs’ home, I’d get up every morning, and we’d drive in his VW Bug up to Neil Young’s house in the hills to record After the Gold Rush. I was in LA with Grin, but I remember saying to David: ‘It’s also nice not to be the band leader so that your only issues are musical.’ I learned that at a young age. So when opportunities arose to be in Ringo’s All-Starr Band, Bruce’s E Street Band and other bands with Neil, I recognized how valuable that was for my musical spirit. A lot of solo artists don’t want to do that and it’s OK, but I do. I thrive being in a great band with great people and not having to be the band leader, which I’m also quite happy to do.”

Over the years, Lofgren has successfully navigated both creative courses. Between 1971- 73, he released four albums with Grin, composing all the material, including two songs that remain staples of his shows: “Like Rain” and “Believe.” He has gone on to record more than two dozen albums under his own name, the most recent of which, Mountains, was released earlier this year.

The new project came together during lockdown, during a period when the guitarist explains, “I challenged myself to write whatever was going on with me. With all the crap that’s been going on the last four or five years with COVID and politics, it threw me for a loop. I had this PTSD back to the ‘60s with the Cuban Missile Crisis, the assassinations, the Vietnam draft, all that stuff. Making Mountains was a therapeutic way to work through it.”

While Lofgren sings and plays a range of instruments on the record, the sessions also provided an opportunity to reconnect with many of his longtime friends and colleagues, including: Starr, Young, David Crosby and E Street Band alum Cindy Mizelle. Bass legend Ron Carter makes an appearance as well.

Lofgren has yet to tour in support of Mountains given his commitments on the road with Springsteen. “I expect that will happen, but for now, I’m completely immersed in E Street,” he explains. “Then if there’s an opportunity, I hope Neil takes Crazy Horse out and I get to play with him. That’s the rock-and-roll dreamer in me. Music is the planet’s sacred weapon, it’s a source of comfort and inspiration. It heals and unites people. So I’m thrilled to be at it after 55 years and blessed to have this new record.”

Over the years, you’ve hosted something called the Blind Date Jam, which highlights improvisation by bringing together musicians who then collectively create in the moment. How did that initially come about?

It’s something I want to pursue more. The theme is: You know who you’re going to play with, but you don’t know what you’re going to play. I just throw out a jam idea or a different version of a song they’ve never heard. Then I count off and we go at it. I had a great one with just me and Mike Smith, an extraordinary pedal steel player who lived here in the area.

I remember when I recorded Tonight’s the Night with Neil Young and David Briggs, my two greatest mentors, it was an anti-production record and also a wake album because all our heroes and friends were dying. We were in a rehearsal hall in East Hollywood. They knocked a hole in the wall, ran a remote truck line and said, “You’re going to be playing and singing live, and when Neil gets the vocal, you’re done—no one’s allowed to change a note.” Not only that, but they didn’t want us to know the songs too well. That’s because musicians will think, “Oh, here’s my great part for the verse.” Then every time there’s a verse, that’s what you’re going to hear.

So, we’d drink tequila and smoke a little Thai weed from dinner until midnight to commiserate. We’d lost Danny Whitten and Bruce Berry, as well as Hendrix, Joplin, Brian Jones and all these people. The hippie freelove movement of the late ‘60s turned pretty dark.

Neil would show us three or four songs, then we’d go play them, and me and Ralphie [Molina] and Billy [Talbot] and Ben Keith would sing. We didn’t really know them, but that was the theme. That type of approach was cathartic. The idea was we don’t want you to know what you’re doing, just stay down in it and react with your musical skills, not your mind. The music and the madness, especially when we hit the road, healed us and helped us survive the grief and the rage of all these deaths around us.

To fast-forward, on a lighter note, I thought that the musical idea of people playing together who really don’t know what they’re going to do remains a brilliant idea. I’ve been on bandstands for TV shows where we were told, “Hold on. We’re not ready for you.” So the band started quietly jamming and I’m going, “Damn, people should hear this.”

So I want to pursue that again. My vision is it would be an incredible cable TV thing and people would see a lot of their heroes. The charm for great musicians is that they don’t have to prepare. There are no charts and no setlists. They would just show up with whatever instruments they wanted. Then somebody, including myself, might throw out a riff and get to expand on it for two minutes or 20 minutes.

In applying that general idea to the E Street Band, have you ever been stumped when Bruce sees a sign in the crowd and calls an audible? If so, how did you respond?

It happens, and it’s battle conditions. The road crew’s frantically looking for lyrics to put in Bruce’s teleprompter in 18 seconds, while we work out an arrangement of a song we’ve never played together. So you cut to the chase.

A great example—it’s a famous one because we had the horns—is “You Never Can Tell,” a Chuck Berry song that I wasn’t aware of. Bruce is singing lines to a horn section and he wants them to play it as a section. I’m like, “Oh man, I don’t know this song.” But Stevie mentions it’s a Chuck Berry song, so since I’m in front of an audience, rather than ask, “What’s the chords? What’s the arrangement?” I think, “I’ve got two guitar players, Bruce and Stevie, who know the song. So all I need to know is the key and I’m going to play bottleneck blues.”

So I push the bar until a note works, and I realize what key I’m in. Then I play blues on the bottleneck. You just instantly find solutions.

It’s the same thing with Blind Date Jam. When you’re with people you admire, you want it to work. There’s an intensity and inspiration born of creating something live with people you respect that leads to moments you don’t see in a rehearsed setting.

Since you mention bottleneck, you also play pedal steel and lap steel to fine effect on Mountains.

On World Record, the last album that Rick Rubin produced with Neil, that was the first time I broke out the pedal steel with Crazy Horse. I began playing lap steel and oddball instruments. Neil and I are both swing men jumping around from any keyboard to any guitar. It was a joy to make that record.

I hope, down the road, we get to go on tour. That was our third record in four years. It was very exciting to be playing with my oldest musical family, Crazy Horse. When Stevie came back to the E Street Band in ‘99, we didn’t need three guitar players on every song, so I went and took lessons on pedal steel, Dobro and lap steel. I fingerpick a lot and I love the feel of flesh on the string. So putting metal in between was very uncomfortable and foreign. But one of my great teachers, Mike Auldridge, rest his soul, said, “Nils you’re pretty adept at fingerpicking, but you’re going to regret the sounds you can’t make without the metal on your finger. I advise learning now.” So I did, and I got a six-string banjo. Putting those sounds in Bruce’s toolbox was useful because we don’t need three guitar players on every song. Bruce writes authentically in every genre, so it’s nice to have those new sounds in the band. Of course, I bring it to my own records, including Mountains.

In Bruce’s memoir, he mentions that he first met you at the Fillmore West on an audition night. I assume you were out there with Grin. What are your recollections of that evening and did you cross paths with Bill Graham?

I knew Bill Graham as the historic promoter with giant light shows the size of a movie screen, who usually had two or three great acts on every bill. This was one of his famous audition nights, where the locals would get in free and pay a buck for a beer. There were a dozen bands playing 20 minutes each, hoping to get a job as an opening act. Bruce was there auditioning with Steel Mill and I was there auditioning with Grin.

Bill Graham was this mythical character and we were there all day hoping to get a little soundcheck. Then I overheard Bill talking about a basketball game in the afternoon, so I asked, “Mr. Graham, can I come and play basketball?” I love the game. I went with him to this five-onfive crazy intense basketball game in the afternoon, auditioned in the evening and, eventually, Grin got some opening-act jobs. I’m sure that Bruce did as well. But that was my first exposure to the greatness of Bruce, and I’ve followed him ever since.

Did Bill Graham have game?

Bill Graham had great game. He was also super intense and bordering on a dirty player. If you fast-forward years later, the E Street Band was playing the Cow Palace. Bill had a basketball court set up and he casually asked if we were interested in a three-on-three game. He had his ringers—great players—and we took them on. It was me, Kevin Buell—who is Bruce’s tech—and Jon Foster, who was on the road with me for years. I’m a good player, but I’m 5’ 3”.

We got in this vicious three-on-three game and we beat Bill. There was steam coming out of his ears but even if his instinct was to say, “You’re fired, you can’t play tonight,” it was Bruce Springsteen, so he wasn’t going to fire us. [Laughs.]

Then in 1988, we were on the Amnesty [International] Tour with Sting, Peter Gabriel, Tracy Chapman and Youssou N’Dour. That’s when me, Branford Marsalis and Miles Copeland—Sting’s manager, who didn’t know how to play— took on Bill, Tracy Chapman and Elliot Roberts, Neil’s manager. Elliot was one of my dear friends, rest his soul, and a great basketball player.

We thought it would be a friendly game, but they made it clear it wasn’t. On the first couple possessions, Tracy drove right into me, put me on my ass and scored. Then me and Branford huddled up with Miles Copeland and said, “We’ve got to be more serious here.” Miles was strong, he just didn’t know the game. So Branford said, “When you get the ball, don’t let anyone take it out of your hands. Grip it with a death grip, then get it to me or Nils and play defense.” We wound up beating them, and Bill was livid. [Laughs.]

Elliot was a great player, we played a lot in the parks of LA and we both know how to lose and win. But when this great book about the tour came out, they talked about the famous three-on-three game—I think it was at a gym in Rome—except in the book they win. So I called Elliot and said, “What the hell is this shit? We beat you. You were the ones who decided we were going to play for blood and we beat you anyway. But it says here that we lost. What the hell is that? That’s just a flatout lie.” And Elliot said, “Well, Nils, in Hollywood, we call that spin.” [Laughs.]

Did you participate in any other memorable games on the road?

The camaraderie was incredible on that tour. We’d get baseball mitts and play catch. We had a ping-pong tournament for six weeks—the top three were myself, Roy Bittan and Manu Katché, Peter Gabriel’s drummer, who is an extraordinary guy. We had a tennis tournament and Roy Bittan won that.

Since we were on this high-end tour, Branford and I would call ahead and ask the promoters to organize threeon-three, five-on-five games. Branford is a great player and an athlete. A little known fact: He was a middle linebacker during college.

We played all over the world. Sadly, because of my two metal hips, I can shoot around, but I can’t play that vicious three-onthree anymore.

Returning to Mountains, you co-produced the record with your wife Amy. How did that originate?

We were at home in Scottsdale, Ariz., and we were scared of COVID. This was before the vaccine. Amy and I both have health issues, so all the little bars I play weren’t safe. There was no protocol.

So I would go out to my home garage studio, put on Albert King, B.B. King, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and just play blues. That was a nice hobby and a fun musical release. I loved being home with Amy and the dogs, and our son Dylan would come over with his dogs every day.

That was great, but it bothered me that I was not performing in some fashion because that’s what I do. Out of all the jobs I have as a musician, what I’m best at is performing live. I get an energy from an audience I don’t get anywhere else.

So after a while, I thought, “Well, you’re not going to tour and you can’t jam the blues with Muddy Waters, even though it’s fun.” So I challenged myself to write an album and share it. Jamie Weddle, a great engineer and friend who has been working with me here for over 20 years, came over. We both tested and wore masks unless I was singing. Then, slowly but surely, we got Mountains done.

While I was writing and recording, Amy was covering all the other bases. I felt she deserved a co-production credit. She’s not impressed by fame and she’s not impressed by Hollywood, but she loves music, and she had some valuable, refreshing takes throughout the project.

Since you note that it came together gradually, was there a moment in the process where you felt like something shifted and the album took on a momentum of its own?

Very early one morning, I said to myself: “You’ve got to start writing in earnest.” That’s when I came up with “Ain’t the Truth Enough,” which I thought was catchy and I had a melody for it. I had this beautiful [Martin] D-35 that Jimmy Caan, the great actor, gifted me years ago in Hollywood. I tuned it to an open G and came up with the riff. Then I thought, “‘Ain’t the truth enough’ can be some flippant, superficial thing or it can be more serious.” I felt I had to do something serious.

There’s been a war on women my entire life, and it’s gotten a lot worse. Amy has been vocal on social media—fighting for women’s rights, children’s rights, democracy, human rights. She’s gotten a lot of bigtime fans from it—people in politics and people who are fighting for the same thing.

So I came up with an idea: “What if a fierce mother had a husband who disappeared, and he’s just come back from the January 6 insurrection? How would she navigate that?” That inspired and excited me, so I wrote it from there. That was one of the early songs that kind of jumpstarted me on the path to getting Mountains done.

Ringo plays drums on “Ain’t the Truth Enough?” Given the COVID complications, I assume he wasn’t in the room with you. How challenging was that to pull together?

Ringo, Kevin McCormick and I played a live track together back on my Silver Lining album in 1991, on a song called “Walkin’ Nerve.” We played it in the room, no baffles, looking at each other. It was incredible. After that, I said, “Ringo, I want to do that again if it’s OK, and I want to do it live.” But with COVID, it was very complicated to get all this equipment to LA with everyone masked, everyone tested. So it was Ringo who suggested, “Nils, why don’t you just flesh it out with instruments so it sounds more like the record you envision and let me play it at home. I do it all the time.”

Of course, I wanted to send it to him with a great bass part. Kevin McCormick put one on with the caveat—“Now look, Nils, once Ringo plays drums, I get to play bass again.” So we sent Ringo a good facsimile with Kevin’s bass and all my parts on it. Then the next day, he called me and was singing the chorus at me, which I thought was a good sign. He said, “I love the song. When you’re ready, send it. I’ll play on it.”

So that’s what he did, and he played brilliantly. There are some people who don’t play to a click, they swing to a click. They’re so comfortable with it, they can lay back, be on top, work with the music they’re hearing, and Ringo’s one of the greats. I mean, listen to The Beatles’ music. It’s the greatest body of recorded music in history, and he’s the engine for all of it.

Just after the album came out, I called him to check in, which I’ve done since ‘85 when we met. So here’s Ringo Starr, The Beatle, saying, “Hey, Nils how’s our record doing?” I mean, what do you say to that? [Laughs.]

David Crosby appears on “I Remember Her Name,” a title that seems to echo his album If I Could Only Remember My Name and the recent documentary about him, Remember My Name. Was there a direct correlation as you were writing the song?

No, it was serendipity, basically. I’ve known David for 54 years through Neil, and we’ve stayed in touch. Then, with the advent of social media and Twitter, he and Amy got to be friends because they both took the piss out of people and stood up for human rights, women’s rights, children’s rights, common sense and democracy. They became friends.

We’d talk once in a while, and at the end of Blue With Lou, my last album [which featured previously unreleased compositions Lofgren had written with Lou Reed in the 1970’s] David said, “Nils, let me sing on your record.” I said, “I’d love to. We’ve got to make that happen with my next batch of songs.”

Fast-forward to when I started writing this story about me and Amy having 15 years between our first and second date, which is true. Then, when I had the song, “I Remember Her Name,” I laughed at the similarity to the title of David’s great movie that I loved watching—it’s tragic and beautiful. So I reached out, told him about it and then I sent him a demo to check out.

I knew that with the Amy connection, the title connection and our long history, he would be great for that. His son James engineered it, and he sang beautifully on it.

You have a Rockality section of your website, which features videos in which you tell stories and then perform. If you’ll allow me to pitch one, I’d love to hear you talk about how you first came to perform a backflip on stage with your guitar.

That’s going to be a Rockality story. I’ll give you the highlights, though. I hit the road at 17 professionally with Grin. By 18, we were in LA, and I was making After the Gold Rush with Neil. We were under David Briggs’ wing looking for record deals and we got one with Spindizzy, a division of Columbia, from Clive Davis. At that time, the record companies would help you with tour support, meaning you made very little money, but they would help you open for bands all over the country. We loved that because we took to playing live.

We opened for J. Geils a lot, and they were incredible. When I started, I would just stand still, so I could concentrate on playing and singing. I wasn’t jumping around freely. But I thought to myself: “What can I do that’s not fake to compete with Peter Wolf and J. Geils, who are extraordinary.” I was a gymnast in junior high, which wasn’t that long ago back then. So I asked my old coach at the YMCA where I trained, to get a little mini tramp and help me learn how to do a backflip without my upper body while I held a guitar. Then I put it in the show.

I did that flip from 1969 to 1985, halfway through the Born in the USA tour. It was a great stunt that obviously paid off.

One of the first times I recall doing it was in Tampa, opening for J. Geils. There were 3,000 college kids with a buzz on, booing us—throwing bottles at us, screaming for J. Geils, which we were used to. Before we went on, the promoter said, “Now look kids, if you play a second over half an hour, you’ll never work in Florida again.” I was like, “Look dude, we understand. I’ve got a $16 Casio watch on my wrist. We promise we’ll play under 30 minutes.”

So we play, and at the end of our show, I do the backflip in front of an audience with the guitar on. We walk offstage and go down into the bowels of this arena. Then the promoter comes screaming into the room, “Get back out there! Get back onstage!” We’re like, “What are you talking about? They booed us. They were throwing bottles at us.” He said, “Yeah, but when you did that flip, they went berserk and they’re starting to throw chairs. They’re gonna destroy the arena. You must go back out.” I said, “No, we’ve got to work in Florida again.” [Laughs.] And he said, “You’ll work in Florida again.” It was panicked.

We went back out to a raving cheering, clapping, yelling crowd who now loved us. I thought, “Welcome to show business.”