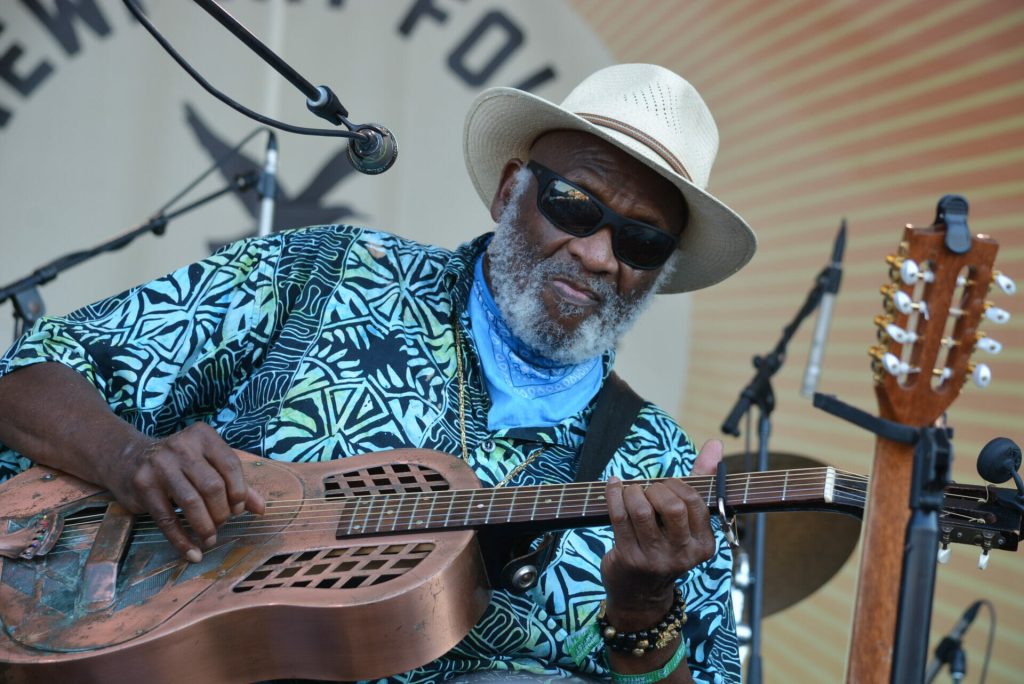

photo: Dean Budnick

***

“My parents really did meet at the Savoy Ballroom,” Taj Mahal says, echoing his spoken-word intro to “Stompin’ at the Savoy,” the opening track on his latest record. That initial encounter took place in 1938 when a young Ella Fitzgerald was the lead singer with the Chick Webb Band and appeared regularly at the famed Harlem nightclub. “They knew Ella and they would see her there. It’s pretty fantastic. That was the Black American palace where everybody went to dance and socialize.”

On Savoy, Mahal explores the big-band era of swing jazz. This release is the follow-up to Get on Board: The Songs of Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee, his collaboration with Ry Cooder, which won the 2023 Grammy for Best Traditional Blues Album. Indeed, even though Mahal has been inducted into the Blues Foundation Hall of Fame and received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Americana Music Association, he has embraced the sounds of multiple regions and genres over the course of his illustrious career.

As he considers the material on Savoy, Mahal reflects on the significance of the songs that he first encountered in his youth. “I can remember us standing next to my father’s record player with my brothers listening to Louis Jordan do ‘Caldonia’ and we would each sing different parts of the song,” he says. “Records in those days were like musical messages culturally from your aunts, uncles, cousins and friends who you hadn’t seen in a long time. We stayed in touch with one another through the music.”

Throughout Savoy, you’re not only looking back at your formative years but also working with John Simon as your producer for the first time, after he toured in your band for a stretch in the 1970s. How did it all come together?

John was inspirational in kind of nudging it along. We’ve been talking about music for a long time, just sending different stuff back and forth every now and then. We’ll send stuff that we’re excited by—Bill Evans, Gil Evans, Erik Satie, [Andrés] Segovia, all kinds of music.

I’ve done other things over the years where I’ve used my jazz chops. There’s a record called Conjure where we put the poetry of Ishmael Reed to music. But John always said that he would like to do something with me. So I finally decided that I wanted to stretch my wings in this direction.

John’s an exceptional musician and he’s done some really great work, but he gets out of the way and lets the music happen. He worked with Leonard Cohen, Blood, Sweat & Tears, Janis Joplin, and the great records by The Band. As much as I love all of those, it was a record with the Canadian philosopher and seer Marshall McLuhan that really blew my mind.

The ideas on that record, The Medium Is the Massage, and his books like Understanding Media, are still relevant today.

Everything that we’re doing now, that guy foresaw back in the ‘60s. I remember going up to Columbia Records and into this guy’s office and he said, “If you see anything you like, take it.” Something drew me to that record, so I asked him if I could have two. That way, I could put side one and side two on my turntable, and I could listen to them both in continuum.

I would pull the shades in my house and stretch out on a sleeping bag or some pillows. Then I’d close my eyes, put that on and imagine what this guy was talking about. John was kind of surprised when I first told him it was something that I really liked. But I think people should go back to it just to listen and to realize, “Wow, this is something that’s been realized.”

In John’s book [Truth, Lies & Hearsay], he describes touring with you in the early ‘70s and being amazed that you could identify breeds of cattle. Do you have a recollection of that?

Every time I get out in the country, I’m looking at the land, seeing what people are growing and what kind of animals they’ve got. I did three years of vocational agriculture in high school from the 10th grade to the 12th grade, and every summer vacation, I was working on a dairy farm. I went to the University of Massachusetts to the Stockbridge School of Agriculture. I majored in animal husbandry, and I minored in veterinary science, agronomy and dairy technology.

I thought, “There are two things that Africans brought with them to the Western World. One of them is agriculture, and the other is music. Those are two things that people are not going to do without. People are always going to eat and they’re always going to want to hear music.”

Bringing those together, I know people who still speak fondly of your barbeque efforts on the H.O.R.D.E. tour.

Instead of riding with the musicians, I wanted to ride on the bus with the techs, the roadies and the gophers. Those are the hardest working people in show business. When I saw what they were eating—Taco Bell and that kind of stuff—I asked for a stipend. I got a couple of these water smoker grills that look like R2D2. Then I’d send a runner around every day to get me a couple of big salmons, some chickens, some veggies and some other things. I would marinate them to get them all going, and then at nighttime, when those guys got done, they had some real food to eat.

I would grill everything— tomatoes, fruit, zucchini, pineapple. I had a big pan, and I would put spices in there with the leftover onions and some garlic. Then I would throw some brats in there so that everybody could grab something. I did that on the Widespread Panic tour, too.

You’ve said you first heard “My Baby Done Changed the Lock on the Door” [which opens Get on Board] on a Louis Jordan record. Can you talk about the connective tissue between that album and this one?

They connect just because they’re all a part of the same culture. When Alan Lomax and John Work went down to Coahoma County, Miss., [in 1941-42] to record the music—that’s when everything was changing down there and people were leaving the plantations for work up North— they would go into all of these different juke joints and see what was on the jukebox. Instead of it being Robert Johnson and Elmore James, it was Duke Ellington and Count Basie.

Sonny and Brownie didn’t only do the more country-type blues. Brownie took elocution lessons so that he could get rid of his Southern accent. That way he didn’t mumble and speak in those low tones that the dominant culture has difficulty understanding and spent 80 years parodying with blackface. But Brownie also did a tune called “Did You See Jackie Robinson Hit That Ball?” This was Brownie with a band—he had piano, bass, horns and everything in there.

So everybody was listening to everybody else and the general public was into good music. That’s what I’m trying to do here. This isn’t an echo. I believe that if it was good back then, it’s good now. People can relate to it.