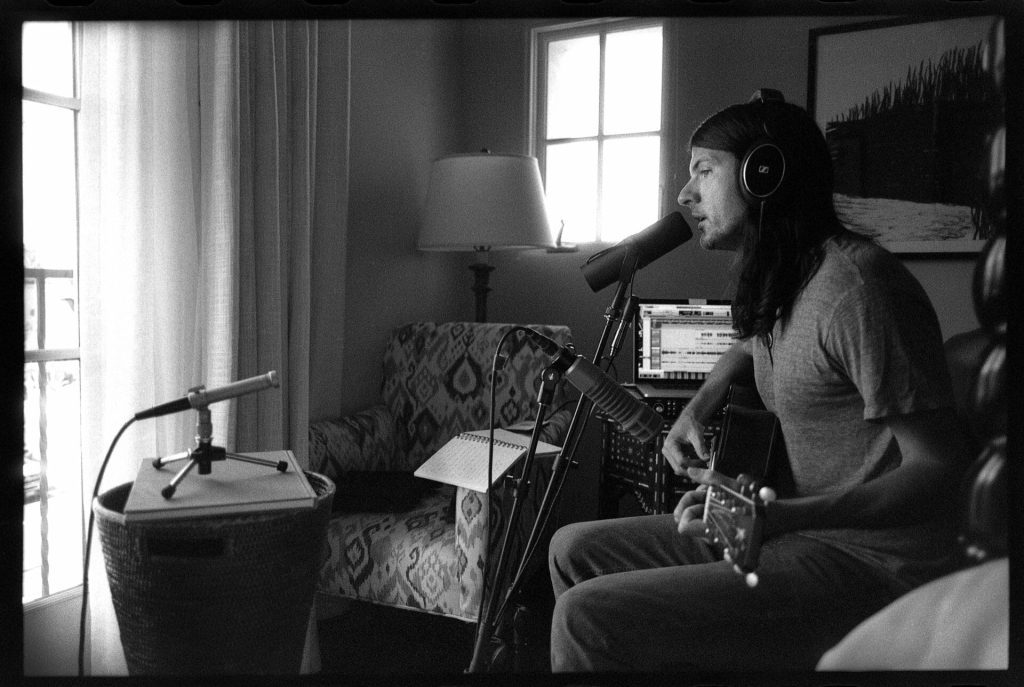

The Avett Brothers co-founder pays tribute to Greg Brown, an artist who enlightens and inspires.

***

The 1980s were probably not the easiest time to be a folksinger. Between the shiny, new electronically produced textures of pop music and the generally celebrated pomposity of pop culture itself, there was seemingly little reverence, or room in the charts, for songwriters searching for the truth using poetry and an acoustic guitar. They were out there though—a dedicated gaggle of traveling troubadours, slugging it out with destiny and modernity in coffeehouses and bars, restaurants and tiny theaters, just as they had done prior to the folk revolution of the early 1960s. (Though there wouldn’t be any national interest forthcoming for those leaning toward what we now call “Americana,” save for Mr. Mellencamp, the exception that perhaps proves the rule.) Through this period and well beyond, folk artist Greg Brown quietly wrote and recorded some of the most profound, engaging, heart-rending songs of the past 40 years, sketching masterpieces on a fairly regular basis regardless of (and, of course, due to) his place within his time, as any great author arguably does.

I was introduced to Brown’s music when I was 15 years old, thanks to an episode of Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion where he performed a song called “Boomtown.” I liked it, but my dad loved it, so we got ahold of The Live One on CD, and I quickly became enamored with it. I understand now that it wasn’t just the songs that brought me in. It was the unending supply of absolute personality in that voice, those stories. Brown’s vocal delivery was honest and devoid of affectation. If there was any self-awareness to it at all, then it only served the humor and humility of the most vulnerable lyrical passages. What I heard was a poet with the most natural and easygoing command of his range, emotional narrative, language, ego, failures and passion. The Live One was an interesting introduction because it showed Brown first as a vibrant storyteller, able to do in musical performance what so many of us struggle to do on stage and in life—that is, to be fully present and act and react with the immediacy of one who truly knows himself.

I would later come to appreciate Brown’s sheer abilities as a sonic craftsman and lyrical expressionist through an astounding body of work that spans in years roughly the same chapter in history as my lifetime. But at 15, when I first heard him sing, I only recognized a great voice, some great songs and a committed-to-tape sincerity—all elements and occurrences that I had apparently already begun lifelong obsessions with.

As in life, artistry that comes across as exceedingly simple in form or theme can often hold an immense and inarticulable depth—think Robert Schumann’s Album for the Young, Mark Rothko’s immense floating squares of color, Mary Oliver’s single stanza odes, God’s blue sky. What I have learned by absorbing so much of Mr. Brown’s music is that a song worth singing is also worth shielding from the clutter— and there are many varieties of clutter. Even the light of the most genuine inspiration can be dimmed in practice by technical fervor, overthinking, excessive aesthetic decoration, technological interference and/or egoic long-windedness. There are so many ways to get in the way of a great song, and I feel that one of the great qualities of a great songwriter is the ability to, more or less, let it be. A great songwriter’s job is to channel or chase their wild and lovely inspiration to its natural end, share it as well as they can in that moment and then simply let it be what it is. Brown’s songs remind me of the beauty of this event of human life and also not to make too much of a fuss about it—that though love in any form can be serious business, it is also important not to take it too seriously.

When I was a teenager, my overall response to music was to hear it, judge it and subconsciously or overtly rank it by categorizing it as “good” or “bad,” “pure” or “commercial,” “cool” or “corny.” It did not occur to me that this judgmental approach to artistry is largely a distraction. Part of why I hold such reverence for Brown’s songs is that they contributed greatly to my growth as a listener of music and a participant of art. His music stands as a body of work that kindly ascends all of the aforementioned adjectives, pointing out that what’s interesting about art is not whether something is pleasing to the ears, but rather that an artist is sharing a space with you—offering without force—so that there may be a space to connect with one another. On the surface, I still categorize his—and all—songs, but now I can see that even music that I am not drawn to has undeniable worth as an expression of a beautiful soul, whoever it might be. I suppose Brown’s songs do for me what any masterful artist has the power to do with their work—to radically widen the perception of those they inspire.

If you have never heard any of Brown’s songs, then I recommend going to The Live One straightaway—there will be time later for In the Dark With You, Further In and Songs of Innocence and of Experience. Set down your phone, close your eyes, clear your mind and listen to the song “Spring Wind.” Within the first introductory moments, you might experience that rare and wonderful feeling that you sometimes get when you hear a song that you’ve never heard before, or when you hear a voice for the first time that is nevertheless unmistakably familiar. That is how I felt the first time I heard Mr. Brown, a feeling that I still encounter, on some level, each time I hear his recordings. It is the expressly human warmth that is ever present when hearing from a friend.

***

Seth Avett is the co-founder of the North Carolina-bred roots act The Avett Brothers. He released a tribute to one of his musical heroes, Seth Avett Sings Greg Brown in November.