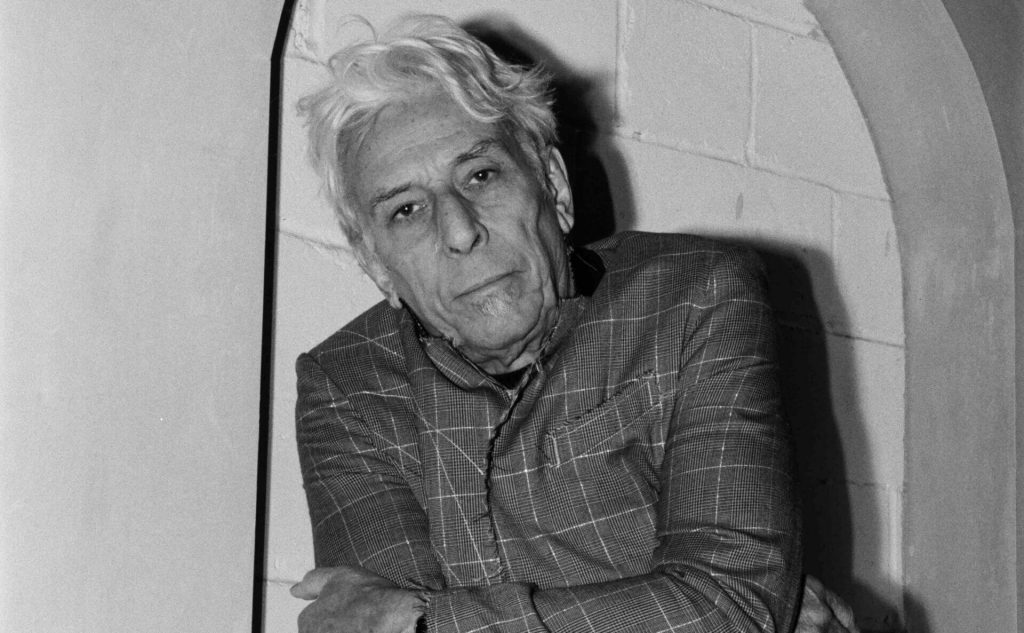

photo: Marlene Marino

***

John Cale is a master at balancing the past and the present. As one of two surviving members of The Velvet Underground’s original lineup, the Welsh-bred composer and multi-instrumentalist is acutely aware of his former group’s legacy—and has helped bring their storied songbook to a new generation of musicians. In recent years, he’s taken part in a Grammy tribute to The Velvet Underground, worked with Todd Haynes on a Velvet Underground documentary and participated in indie-centric celebrations of the pioneering proto-punk outfit’s debut album, The Velvet Underground & Nico around the world. At the same time, he’s also continued to thrive on the fringes of alternative music— exploring new and exciting creative avenues in the electronic and avant-garde worlds, performing on the train tracks that divide North and South Korea in the DMZ, staging shows in China after being denied entry for decades because of his documented support for Tibet and composing for an orchestra of flying drones.

He’s also a consummate collaborator and producer who has worked with the likes of Patti Smith, The Stooges, Siouxsie Sioux, Squeeze and Little Feat’s Lowell George during his storied career—helping connect Brian Eno with Talking Heads along the way.

“People jumped at the opportunity to do it and I’m glad they did,” Cale says of the range of performers who joined him at his VU tribute shows in 2017. “It changed from show to show. When we did it in Europe, for instance, it was a different group of songs. It still worked out as an expression of their variety of tastes and what they wanted to do.”

Cale’s new Domino release, Mercy—his first set of new songs since 2012’s Shifty Adventures in Nookie Wood—was written against the backdrop of Donald Trump’s presidency, Brexit, COVID-19 and the climate change crisis. The 80-year-old musician explores those dark themes with the help of a cross[1]generational cast, including Fela Kuti’s longtime drummer Tony Allen and younger acts such as Weyes Blood’s Natalie Mering, Laurel Halo, Tei Shi, Animal Collective’s Avey Tare and Panda Bear, Blood Orange’s Dev Hynes, Sylvan Esso, Actress and Fat White Family. “I just let them breathe in their own space,” Cale says.

“I let them give some life to what was a new song to them. And, by the time we finished, it was a new song for me, too.”

Mercy is your first full-length release in almost a decade. For how much of that time were you working toward a new LP?

Well, considering there was the pandemic right in the middle of it, it took about two and a half years. But it was longer than I had hoped—I wanted the songs to have some life to them. The titles of the songs and the artists that I asked to join me on the adventure helped with that.

I didn’t add the artists until the very end. I started off with the entire album more or less finished—the songs were finished—and then I got on to figuring out which songs fit which artists. The songs didn’t change that much after I gave them to [the different artists] but they had some new life. And that’s how it went on. One of the more abstract songs with Darren [J. Cunningham], “Marilyn Monroe’s Legs (Beauty Elsewhere),” came last. It was a dream sequence of fragments that needed to remain as true to itself as possible. And I built the song as an improv piece centered around these scattered lyrics. The abstraction of it was what got interesting.

You recruited a number of younger musicians who grew up listening to The Velvet Underground and your music, as well as Afrobeat legend Tony Allen, for this project. What was the process of selecting your guests like?

Tony’s a sweetheart. He’s lived his own style of life, but I’d known him from the years that I’d been at Island [Records]. I’d worked with a number of [these younger musicians] before. I’d done some performances with them—there was a Velvet Underground regrouping that happened that I was involved in, and some of them were on that. You never quite knew how their approach to the music would change the music itself. I was very happy with the results

[For Mercy,] it was just a question of pitting their voices around the songs. Animal Collective—they’re a fun bunch of guys to get along with. I love Sylvan Esso, and I like their style of arrangement; Amelia [Meath] and Nick [Sanborn] fit right in.

When you announced Mercy, you didn’t shy away from referencing the darkness of the past few years. How did the pandemic change the album’s scope?

It grew and grew, and it got stronger as we worked on it. It got in everybody’s head—climate change, civil rights and right[1]wing extremism. The entire album is a reaction to the times. Pre-pandemic, it was more political—crushing disbelief that we’d allowed such a thing to happen. Once there was the lockdown, I wondered, “Is it possible to correct course for humanity’s sake?” It’s impossible to strip the political strife from even a love song so it’s always there—just under the surface.

I got back to working on the album the moment I understood we’d be grounded. I’m not good at sitting still. Getting back to the studio was not an option right away because it was under construction, and my gear was unreachable for a few months. When it was clear we were not getting back to any sense of normal, I was anxious to update the album. It needed to have a more defined sense of purpose— not so obscure this time.

You have been performing some of these songs live for quite a while—“Time Stands Still” dates back to 2014. Generally speaking, do you like to test out your material in a concert setting before recording a definitive version?

You’ve got to be careful because some of them have another life all of a sudden, and it’s maybe not the life that you first thought of for the song. I’m starting a tour in February so I’m gonna be gone all year. I’m looking forward to that. One of the things that’s happened with the album is that I’ve had the benefit of time being on my side and I’ve managed to rearrange the songs as they’ve reappeared in concerts. So I got a lot more than just the album—I got some performance ideas as well.

You were a pioneer of electronic music. Is that still the style of music that most excites you?

Generally, it’s the hip-hop side of things that I love—its urgency, its fearless approach, its erratic time signatures, the onomatopoeia. It’s always reinventing itself— sonically, rhythmically. I wanted to try and find somebody with that background to take on some of the songs from the VU—to see how all of that works.

Waka Flocka Flame sampled “Venus in Furs,” but I haven’t found many other hip-hop artists who have wanted to fit their music around the VU material. But I’d like to change their minds about it.