When John McLaughlin and Zakir Hussain first met in 1969, neither had an inkling that four years later they would initiate a remarkable musical project which would remain vital and enthralling for another halfcentury.

McLaughlin had recently relocated from London to New York, where he would join former Miles Davis drummer Tony Williams in Lifetime, before going on to record and gig with Davis himself.

The guitarist recalls, “Like most hippies coming out of the psychedelic period, I began to ask myself all the great questions of existence, and I was looking for answers. Most of us ended up looking East where they’d been addressing these questions for thousands of years—the East in general, but India in particular. The minute you start looking at the culture of India, you will discover the music. They’re fantastic improvisers and amazing musicians. Not for nothing that John Coltrane became very friendly with Ravi Shankar.”

McLaughlin then frequented a Greenwich Village music store called The House of Musical Traditions, which sold instruments from across the globe. Another shop regular was Hussain, an Indian tabla prodigy who had been touring the world with his father, Ustad Alla Rakha, since age 12 and had recently touched down in the United States.

McLaughlin remembers, “I said to the owner: ‘If ever a great Indian musician comes in who would be ready to give me a lesson, please let me know.’ I was hungry to learn the rules and regulations of Indian music in order to be able to play with them. He called me up one day and he said, ‘Well, I’ve got a great Indian musician here and he’s ready to give you a lesson. I told him about you, but he’s not sure what to do because he’s a tabla player.’ I said, ‘Ask him if he’ll give me a vocal lesson.’ So I went down to Greenwich Village, and Zakir gave me a vocal lesson, which was fascinating because I really don’t sing very well. At the end of half an hour, we both started laughing because of how ridiculous and lovely it was.”

That one fortuitous moment could have been the end of their musical relationship, yet three years later, they crossed paths once again. By that point, McLaughlin had founded the pioneering jazz-rock amalgam Mahavishnu Orchestra (after the name “Mahavishnu” given to him by spiritual guru Sri Chinmoy.) Then, in 1972, at a time when Hussain was teaching at the Ali Akbar Khan School of Music in Northern California, CBS asked the guitarist to perform a charity concert and McLaughlin selected the Ali Akbar Khan School as the beneficiary. The two musicians reconnected and McLaughlin invited Hussain to see his band.

The tabla player remarks, “When I walked in, Billy Cobham was hitting the gong, and John was standing there in his whites. Then he started the arpeggio riff of ‘Birds of Fire.’ My jaw dropped and that’s when I saw what sacrilege I had committed by not giving him the reverence he deserved when we first met. I had been sitting in the presence of a maestro at that time, and I didn’t know it. What a fool I was. So that moment of seeing him onstage is when I realized what a great spirit John is. The next day, we played together in Ali Akbar Khan’s living room. We just hit the ground running, and we’ve been running ever since.”

McLaughlin adds, “Within 20 seconds, I realized I was playing with somebody that I had to play with more because he was just too amazing. There was an affinity that is indescribable. This really was the pinnacle. It was the primal experience behind the formation of Shakti. Zakir is simply the greatest. He says we were musicians from the same family in another life, and I think it is as logical to assume that as it is not to assume that.”

The collaborative undertaking that would come to be called Shakti started to coalesce the following year, during a time when McLaughlin was performing with Mahavishu while also learning the veena [a plucked string instrument that originated in India] from Dr. S. Ramanathan at Wesleyan College. Through Dr. Ramanathan, McLaughlin met mridangam player Ramnad Raghavan, who then introduced McLaughlin to his nephew, violinist L. Shankar.

McLaughlin, Hussain, Shankar and Raghavan soon performed a series of local gigs at area schools and churches, utilizing extended improvisation while seeking common musical ground. By the time the group released its debut album—1975’s Shakti with John McLaughlin, recorded live at New York’s Southampton College—Ragahavan had departed to focus on his teaching. However, Vikku Vinayakram, a master of the ghatam who had crossed paths with McLaughlin in India, joined the collective.

“There was never a discussion as to what kind of music we were going to make,” Hussain notes. “We would sit down in John’s living room in his loft and a riff was put on the floor by him or by Shankar. Then Vikku and I looked at the grooves that might enhance that melodic idea. John and Shankar would look to me and Vikku to find rhythmic breaks and ideas that would allow us to hit unison riffs or patterns that would have melody and rhythm meshed together in a fun way. But it was never, ‘Let’s try to make this a jazz form’ or ‘Let’s try to make this a rock beat.’”

“I am a Western musician, and I don’t wish to be an Indian musician,” McLaughlin explains. “All I ever wanted was to know their music intimately enough to be able to sit down and play with them because they are not only wonderful human beings, they’re phenomenal players. They’re basically kicking my butt as we say in the Western world, but that’s exactly what I want in music. I need to be provoked in the right way. Then it’s my job to provoke them. They all love Western music, but I’m the only harmonic instrument. So by bringing in different harmonic aspects, I oblige them to think differently, which is what they also want because they love Western music just as I love Indian music.”

In 1976, McLaughlin decided to step away from the Mahavishu Orchestra to give his full attention to Shakti. “I realized that Shakti was a musical imperative, to the great dismay of my record company,” he discloses.

“The people around him, all the friends and musicians— not the record companies— thought it was great,” Hussain observes. “When we would play a jazz festival, I’d look in the wings and there would be Chick Corea standing there or Herbie or Joe Zawinul or Jaco Pastorius. That’s because we were doing something that they had not heard or seen. As far as they were concerned, it was something unique and special. Having that kind of an environment made it easy for us to sit and do this.”

The initial incarnation of Shakti released two studio albums and toured the globe through the end of the ‘70s. At that point, Vinayakram’s father—who had founded a percussion school in India—passed away, leading Vinayakram to return home and assume responsibility for it. Meanwhile, L. Shankar’s interests shifted and he departed to work with Frank Zappa, Peter Gabriel and then a range of artists in the poprock realm.

With Shakti in abeyance, Hussain and McLaughlin teamed up on other projects until 1997, when the Asian Music Circuit, a nonprofit funded by Arts Council England, made a compelling offer for a 10-date reunion tour. Vinayakram agreed to participate, but L. Shankar never responded to inquiries, so they opted to perform as Remember Shakti, adding new textures with renowned flautist Hariprasad Chaurasi. Some European dates followed, but eventually both Chaurasia and Vinayakram returned to their prior commitments.

McLaughlin recalls, “Zakir and I were sitting there, and I looked at him and said, ‘We have to keep going. We cannot stop now and let this wonderful thing go away again.’”

Remember Shakti continued to evolve with the addition of Vinayakram’s son Selvaganesh on percussion, along with vocalist Shankar Mahadevan and electric mandolin player U. Srinivas.

Then, in 2014, Srinivas passed away due to complications following a liver transplant.

“U. Srinivas was such a lovely player who had first toured India playing classical concerts at seven years old,” McLaughlin says. “He was a priceless jewel, and when we lost him at 45 years old, we were all in disarray.”

As a result, Shakti remained in stasis until the COVID lockdown.

“We were broken inside when Srinivas passed away,” Hussain acknowledges. “His presence in the band was so special, and he was such a divine spirit. We all believed that he was not of this world. He was put here to make us realize that there’s something incredible out there, and he happened to be the key that unlocked it. When he passed, we had no idea what we were going to do. Then when we got to the pandemic, Shankar [Mahadevan], me and John began sending music back and forth, which led to us doing this trio album called Is That So? When that happened, some kind of mending of hearts started to take place.”

In turn, they began to contemplate utilizing a similar process for a full-on Shakti record.

“Since it was the pandemic, it allowed us time to slowly find the strength to face Srinivas’ absence, move onward in his memory and make this record. One of the reasons why it took this long is that it was difficult to transcend that pain,” Hussain reflects. “It also pushed us to do a studio album where everybody got to take some time to input, re-input, chisel, chip and reorganize. That’s the kind of stuff that Shakti never did before. Even when we did our studio albums A Handful of Beauty and Natural Elements, they were all done in a space of three or four days.”

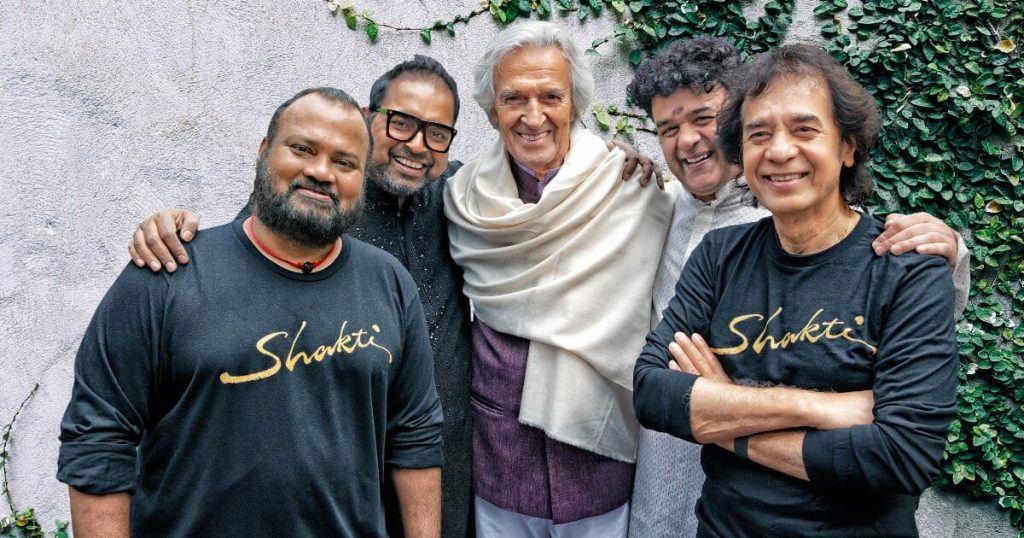

The resulting record, This Moment—which is attributed to the original Shakti moniker— harkens back to the group’s formative era, even as it contemplates a future manifestation of the band’s energy.

“It’s not just the Shakti of yesterday and Shakti of today, but a possible idea of Shakti moving forward,” Hussain affirms. “That’s why you have interesting, synthesized elements, vocal choruses and all sorts of stuff. Also, to bring Shakti back to its origin, I suggested we try Ganesh Rajagopalan on violin. He grew up listening to Shakti and we have played together for the last 17-18 years. He’s definitely added a more lyrical playing but he’s also a big fan of L. Shankar, so that homage is paid on this album. Shakti is now, in a way, a circle-completing sound and experience. Hopefully, it doesn’t end here. There’s a sound foundation for it to be taken further, but whether it will be with John and me and all of us, or it will be another possibility, I don’t know.”

“We’re getting up there, which I say with a laugh. It’s quite possible that this will be the last time we tour together,” the 81-year-old guitarist attests, shortly after explaining that he has been able to circumvent a debilitating arthritis in his right hand and wrist through meditation. “We really are only here by absolute love of each other and each other’s music. It’s a thrill and pure joy every time I sit down with these gentlemen.”

In January, during the Mumbai stop on Shakti’s 50th Anniversary tour, a familiar face rejoined the circle, as Vinayakram appeared for two songs. “We had tears in our eyes,” Hussain shares. “It was a volcanic emotional moment to have him there onstage with us. It felt so satisfying to watch that energy, that love, that hug the audience gave to him and to all of us. It felt like the audience had been holding it in their hearts for decades. For us to be as one, enjoying that hug—that ecstasy—was the moment of the India tour.”

“It still feels like a group of like-minded people who are addicted to the same intoxication, ecstasy and joy,” the tabla player adds. “That’s where our heads are at. We’ll say, ‘OK, we’re going to sit together to work out arrangements that we’re going to play onstage.’ Instead, we end up playing a song for an hour and a half in a rehearsal, just having fun, enjoying ourselves and totally forgetting that we’re putting together material for a concert. What’s unique and magnetizing about Shakti is that kind of hang, where we embrace each other physically, mentally, musically and rhythmically.”