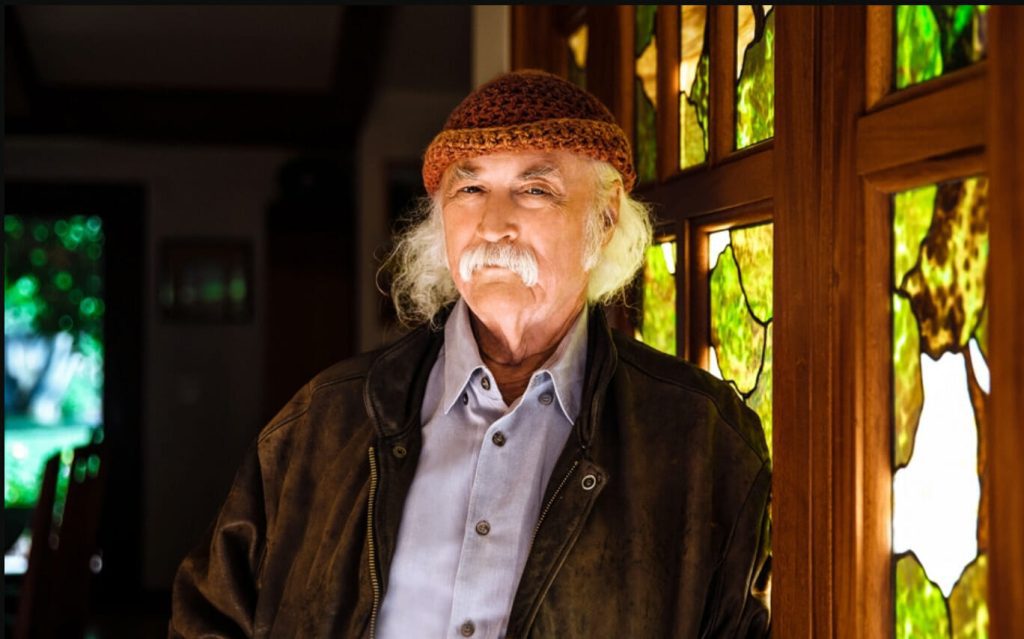

photo: Anna Webber

***

[Author’s Note: Two weeks ago, I had the good fortune to speak with David Crosby. He was animated, engaged and opinionated. It was classic Croz. The piece appears in the next issue of Relix but due to yesterday’s tragic news of his passing, we’ve decided to share it today.]

***

“We were feeling very confident,” David Crosby says of the mood preceding his Dec. 8, 2018 performance with The Lighthouse Band at Port Chester, N.Y.’s Capitol Theatre. “The tour had been a success, this was the last show and we’d sold it out. Everything had been building toward what ended up being one of those magical nights.”

That alchemy reverberates throughout the new CD and DVD David Crosby & The Lighthouse Band Live at the Capitol Theatre. The group takes its name from Crosby’s 2016 album Lighthouse, which was produced by Snarky Puppy’s Michael League and also features Becca Stevens and Michelle Willis. The quartet reconvened two years later for Here If You Listen, furthering their initial bond by delving into some collaborative songwriting. Live at the Capitol Theatre captures the band on the road in support of the second album, highlighting their bright vocal harmonies, spirted interplay and melodic ingenuity. In addition to the compositions that originated with the group, Crosby also dips into his catalog of Crosby, Stills & Nash material, along with two songs from his vaunted 1971 record, If I Could Only Remember My Name. (That album also supplied the title to the award-winning 2019 documentary Remember My Name.)

The past few years have been a particularly fecund era for the musical iconoclast, who has released three studio records in partnership with his son James Raymond—2014’s Croz, 2017’s Sky Trails and 2021’s For Free—juxtaposed with his Lighthouse Band albums. While Crosby had indicated he would be retiring from the road, in late December he revealed that he was back in the studio with Raymond, Chris Stills—who is Stephen Stills’ son—and some additional familiar names, including James “Hutch” Hutchinson and Lee Sklar. The indefatigable artist then tweeted, “Dare I say it? I think I’m starting yet another band and going back out to play live.”

Before we discuss Live at the Capitol Theatre, I’d like to jump back to a lingering question I’ve had ever since I saw Remember My Name. The film opens with you telling this remarkable story about Coltrane bursting into a bathroom while soloing, at a time when you were in there taking solace from the intensity of the music. Did he specifically follow you in there?

No, he didn’t know I was there, and he couldn’t have cared less. He didn’t follow me into the men’s room. He went into the men’s room because it sounded good in there. It was a tile men’s room, and it had an echo.

This was a club on the South Side of Chicago. It was maybe a thousand seater. He wandered off the stage while he was still playing. He wasn’t through with the idea. Then he decided that he liked the sound of the men’s room, kicked open the door and walked in while he was still playing. [Laughs.]

Your reaction was initially prompted by Elvin Jones [Coltrane’s drummer], who got into your head.

Elvin Jones scared me to death. I was extremely high and the intensity drove me up against the back wall. Then, finally, I had to get a little breath of air in the men’s room. I was just looking for a moment of relative peace and calm compared to being in the middle of Elvin Jones’ drum solo, which was not peaceful or calm. And then boing! It was pure accidental karma. But it was so good. I’ll never forget it. Ever. [Laughs.]

Let’s turn to your songwriting, as it applies to The Lighthouse Band and even this new project you’ve just announced. Will you write with a specific personnel in mind or is your focus on the song itself?

I’ll write without a project in mind. There’s a strange chemistry that happens with certain words that will work together and seem magical to me. They seem to have a really potent effect and then I’m on the trail. I’ll say, “Wait a minute, this is a lyric,” and then I’ll follow it. But I don’t go into it knowing where it’s going to go. I have no idea what I’m gonna write. I have no idea if I’m gonna finish the song.

At what point during this process does a narrative come to mind?

It starts to happen as soon as the words begin to connect with each other. At first, I’ve got four words that I really like. Then all of a sudden, I’ve got 16 words and I’m into the song. Usually, it starts with a core group of words that evokes some kind of magic for me. Then it goes on from there.

At least that’s how it always did work because my process has changed. Nowadays, I’ve got writing partners like my son, James Raymond, who is, if anything, a better writer than I am. Also my friends and partners Michael League, Michelle Willis and Becca Stevens are really accomplished writers. What I do now is I send them a scrap, and that scrap generates a song within them. They’ll hear it, figure out what they think I’m talking about, and then they’ll say, “Oh, I’ve got something to say about that.” And they’re on it.

When I wrote “Wooden Ships” with Kantner and Stills, that was the first one where I realized, “Wow, wait a minute. I don’t have to do this by myself. There could be a chemistry here.” That’s developed to the point where now, in my old age, I write more with other people than by myself. And I love it.

In terms of creating that initial scrap, will you typically compel yourself to sit down and try to work up something or will you sort of see it in your peripheral vision while walking through life?

Both. Sometimes if we sit down and have a writing session and we have a purpose in mind, we do it together, word for word. Other times, I send them something that’s about the color blue and they write me back a song about the color green. It’s just unbelievable how the chemistry takes place.

Have you ever written a song that’s been too personal to present to a collaborator, let alone an audience?

I have.

Did it ever find its way out, if only to a single individual?

No, the one I’m thinking of is never gonna come out. Absolutely not.

The live show that appears on your new release includes recent material that you debuted with The Lighthouse Band, along with some older compositions. Do you envision your songs being in conversation with each other in some way or are they more discrete entities?

I would lean toward discrete entities, but the set of values, the set of ethics, the set of ideas is this same body of thought. They certainly come from the same place, though, so there are similarities.

Are there certain concepts you’ve attempted to tackle that don’t lend themselves to song?

Yes. Violence, anger, hatred. The most negative emotions really don’t work in songs. They can work for lunch meat, stupid horror rock, but they don’t work for music.

You often have an acerbic take on politics. Has it been a challenge to express that perspective in your writing?

I write about political stuff pretty strongly when I go for it. There’s one about the Halls of Congress that I wrote not too long ago [“Capitol”]. It’s just that anger itself doesn’t work.

It has to be really clean. It has to be “Tin soldiers and Nixon comin’.” If, instead, you say, “I don’t really like this and I don’t really like that, and I’m really pissed about this, that and the other thing,” then it comes off as whining and sniveling. It doesn’t communicate at all.

If you’re writing a song like “Almost Cut My Hair” or “Long Time Gone,” something where you feel like you have a point to make, then that anger can come in there but you’ve got to be careful with that shit. There is some anger in “Ohio” without any question at all.

Speaking of political subjects, do you feel that music serves a similar communicative role as it once did?

Music can do that, but most of the ways that music communicates these days are shallow. Songs are serving shallow means rather than serving conceptually advanced stuff. If Joni Mitchell were writing songs as good as “River” right now, they might get ignored because what people are listening to now is, “Oooh, baby, I’m so cool. Don’t you think I’m desirable?”

Those songs are all about ego, they’re all about me. They aren’t communicating at the level that Joni can. Of course, she wrote the best songs of any of us. This new kind of consciousness doesn’t lend itself to conceptual advancement or communication. It’s mostly about, “Don’t you think I’m cute?” Well, I don’t think they’re cute. They’re shallow.

I like songs that take you someplace. Joni’s a perfect example. Her song “River” takes you on a voyage. It will expand your goddamn consciousness. It was a major event in my life. The “don’t you think I’m attractive” kind of stuff that comes out now is on a different level—a very surface level—and it’s not the stuff that I care about.

How do you think Blue as a whole would be received if it came out today?

In my opinion, that’s probably the greatest record ever made. It’s without question the best singer-songwriter record that’s ever been made. How it would be received today? It’s too complex. It requires too much thought—“I have to think to get through that. I just want to be told how cute I am.”

Moving on to your collaboration with Michael League, what was your initial connection and how did you first come to work with him?

It started with a friend of mine who was on a bass player site called No Treble. He said to me: “You’ve got to hear this band that’s on here. They’re a big jazz band called Snarky Puppy, and you wouldn’t believe how good they are.” As soon as I listened to them, I had the same reaction.

So I started talking about them on Twitter and somebody told Michael about it. Then he got in touch with me on Twitter and said, “Hi, can I speak with you?” I said, “Sure” and he sent me a number. When I called him, he was in Singapore and he said, “Listen, I’ve got something I’ve got to ask you.” I said, “The answer is yes.” He said, “How could you know the answer? I haven’t asked the question.” I said, “You’re gonna ask me to do that benefit record that you do, and I’m gonna say yes.” And he said, “Yeah, that’s exactly right. Would you really?” I said, “Yeah” and the next thing I knew, I flew down to New Orleans. I spent a week down there with him. And if you spend a week with him, you’ll fall in love with him too.

You also met Becca and Michelle down there. How long did it take for you to recognize that the four of you could coalesce into a band?

About 15 minutes. [Laughs.] I’ll tell you what did it. The time that we spent down there was all musicians caring about music. They didn’t give a shit about the money. They were there doing a benefit. They cared about what they were doing, and they did it the absolute best they possibly could. That was our baby and it felt so right to me. That’s what I had been missing in Crosby, Stills & Nash for a while. I was very attracted to it. Then I invited Mike to come over and stop by my house. In the first three days, we wrote three songs and that pretty much settled it.

Your new live album opens with “The Us Below,” which the two of you wrote for Lighthouse. What are your memories of working with him on that one?

When it comes to writing, it’s hard to predict or even define the process. It’s chemistry. Sometimes you strike a spark in another person and sometimes you don’t. If you do, then you’re writing a song. It’s magic.

That one is a perfect example of what happens when Mike and I try to write together. It just came together, zip!

How about “The City?”

That’s another great example of what can happen. The goal is to make the song be as good and powerful and communicative as you possibly can. But beyond that, it’s important to let go of your preconceptions.

In this case, Michael had a specific idea. He said, “Let’s write a song about New York as a woman.” That was something he introduced. I didn’t bring that into the room but it worked

Thinking about the performances on Live at the Capitol Theatre, was there something about the venue or the evening that evoked a special reaction from the band?

We had been really happy with the tour, so it started prior to that night. Then we arrived at The Capitol Theatre, which is a good venue. It sounds good. It feels good. So on the last night, we were playing the best place. When the four of us listened back later, we all felt that it was exceptional and worthy of being put out.

The acoustics in The Capitol Theatre are really good. Besides that, the vibe is really good—that’s a lot more nebulous, but it’s definitely there. You don’t have to take my word for it. Ask anybody that’s played there.

Jerry Garcia said it was one of his favorites.

I think I remember Jerry saying that.

Two of the songs you performed that night were originally recorded with Jerry [“Laughing” and “What Are Their Names”]. Even though people seem to know so much about him, do you think there’s something that gets lost in translation?

If I were to pick a single musician to speak for all musicians, I would pick Jerry. He had a good heart, and he was bright, which is such a rare combination.

He also had a certain lightness of being, and a joyful melody stream that was just continual. When I sat down with him and we picked up a couple of guitars, the chemistry worked, the parts started to function and, bingo, there it was. It happened every time.

While on the subject of iconic musicians, Miles Davis recorded your song “Guinnevere,” which you perform with The Lighthouse Band on this release. I’ve heard that Miles himself played it for you. The version on The Complete Bitches Brew Sessions is 21 minutes long and rapidly diverges from the initial theme. Can you recall if that’s the one you heard and what was your initial reaction to it?

Well, I didn’t know that he had cut “Guinnevere.” Then he walked up to me on the street in New York and said, “You Crosby?” I said, “Yes.” Then he told me: “I cut one of your tunes.” Well, after my heart started working again, he said, “Do you want to hear it?” I said, “Yeah!” And he said, “Follow that car.”

It was wonderful and delicious, but strange to me. It took me a while to appreciate it. By a while, I mean a span of many years. So that first time, I didn’t quite give Miles the reaction that he had hoped for and he wasn’t all that pleased with me.

Here’s an interesting story about my connection to Miles, though. He was already a hero at Columbia Records by the end of the ‘50s. Jazz was very big and he was the biggest. The story I was told is that when they were thinking about signing us, someone came up to him and asked his opinion. We didn’t know him but somehow he had heard about what we were doing and he told them that they should. So Miles helped get us signed by Columbia.

Starting with Croz, you’ve been on a prolific run. Looking back, can you identify a specific catalyst that set it all in motion?

I had a certain head of steam built up from the relationship with Nash and the relationship with Stills and Nash sort of dissolving. I had a lot of juice in there wanting to come out.

I also had these new writing partners that were so wonderful, particularly my son James. The song he wrote on the last record called “I Won’t Stay For Long?” Holy shit, what a fucking song! The first time he played it for me, he got to the end of that song and I was crying. That’s how good it is.

Any time you have an opportunity to work with amazing people, it keeps you going. That’s why I’m still getting after it. I want to do more.