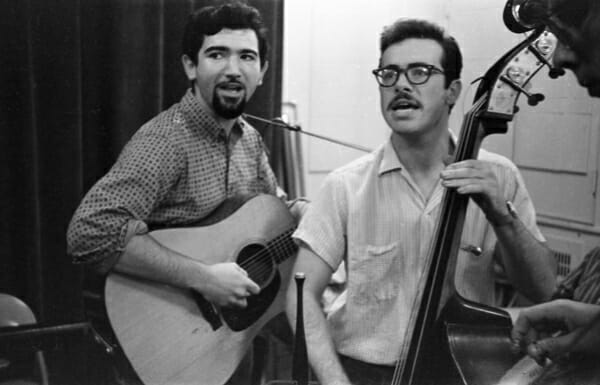

Jerry Garcia and Robert Hunter: Photo Credit Jerald Melrose

**

As we begin The Days Between, the stretch that runs from Jerry Garcia’s birthday (August 1, 1942) to his passing (August 9, 1995), we revisit two articles that touch on the outset of Garcia’s career.

**

“My Name’s Jerry Garcia. I play banjo on the old-timey songs and guitar on the bluegrass songs and do a lot of lead singing too, which I’m not proud of…”

So begins the famed musician’s light, affable introduction to his first-ever studio recording, which took place at Stanford University’s KZSU radio station Studio A during the late fall of 1962. (The date itself remains unknown, although it was likely November or December.) The 20-year-old Garcia appeared with the Hart Valley Drifters, a group that also featured two friends who would remain in his musical ambit for years to come: Robert Hunter (bass) and David Nelson (guitar), along with Ken Frankel (fiddle and banjo) and Norm Van Maastricht (dobro). Their performance has been released on Round Records/ ATO Records as Folk Time, after the name of the show on which they appeared.

Hunter’s own comments from that day explain that the group had previously dubbed itself the Thunder Mountain Tub Thumpers. Looking back on that era, Frankel now adds, “Every time we played, we had a different name. One time, we were riding around playing bluegrass on the back of a flatbed truck with a sound system for this guy running for sheriff of Monterey County [Hugh Bagley]. I think we changed our band name six times during that ride. It wasn’t me doing it; it was Jerry and Bob. I don’t think we had a specific name that lasted more than a month.” As their shifting sobriquets suggest, the players never took themselves too seriously, although they did share a reverence for the music they were arranging and performing.

Frankel was a college student when he first met Garcia at Lundberg’s Fretted Instruments in Berkeley. There, he discovered Jerry making tapes of acoustic music that had long fallen out of print. Frankel was thrilled to find someone who shared a similar interest. He remembers, “I grew up listening to pop music and rock-and-roll when it first came out. But the first time I ever heard that old-time music, I absolutely fell in love with it. Old-time music is the music that came before bluegrass, when they were first able to make records, and they made records from the southern mountain region of the Appalachians. In the 1920s, this was the traditional music that was played in the South and recorded for the first-ever records. Jerry was listening to some tapes there of these records that were 40 years old. People would create tapes. I told him that this was the same kind of music I played, and we just started playing together after that.”

The two began performing in mostly informal settings, just for the pleasure of it all, with Garcia’s pal Hunter typically participating, while various other aficionados of varying skill sets occasionally joined in as well.

Beyond their flatbed set for the aforementioned would-be Sheriff Bagley—the perennial candidate was not victorious in 1962 and would make subsequent unsuccessful runs for mayor, governor and eventually president—the group did sporadically appear in more formal environments. For many years, their only fully documented show was at the College of San Mateo Folk Festival on November 10, 1962, where their setlist included traditionals such as “Roving Gambler” (which opens Folk Time), “Pig in a Pen” and “Nine Pound Hammer.”

A half-century later, intrepid Grateful Dead tape collector Brian Miksis discovered something of an archival holy grail. Miksis had long been searching for recordings of Garcia’s early days, and this pursuit eventually led him to a former Stanford student named Ted Claire (who would go on to play rhythm guitar in Hunter’s short-lived mid-‘70s group, Roadhog). Claire explained that he had recorded live acoustic music in the early ‘60s for his KZSU radio shows, Folk Time and Flinthill Special, and that he had held onto a tape that might be of interest to Miksis. Claire briefly walked off and then returned with a reel that had been languishing in his closet for decades.

Frankel acknowledges that upon learning of this recording, “My first reaction was: ‘I don’t remember making a tape like that.’ Then I listened to it, and I recognized my talking in the introduction. [‘I’m Ken Frankel. I play fiddle on the old-timey songs and banjo on the new-timey songs, formerly bluegrass…’] I knew I played with Jerry a lot and I recognized my banjo playing and my guitar playing. It’s the kind of music I played with Jerry and the same songs. David Nelson recently showed me some pictures from the session, which was pretty funny.”

Folk Time provides a glimpse into the music that animated these five players, all of whom were between the ages of 19 and 22. It includes a pair of songs written by Earl Scruggs (“Ground Speed,” “Flint Hill Special”), a couple of tunes by the Stanley Brothers (“Clinch Mountain Backstep,” “Think of What You’ve Done”), the aforementioned traditionals, and the 16-song set closes out with a version of “Sitting on Top of the World,” which would later find its way into the Grateful Dead repertoire. There were no originals (although Garcia and Hunter reportedly wrote at least one during this era, titled “Black Cat”) because their intent was not to showcase new music. Instead, they wished to embrace and honor tradition at this moment during the incipient folk-music revival.

As for Garcia’s self-effacing assessment of his vocals during the intro to Folk Time, Frankel muses, “I never thought Jerry was that great of a singer. But the main thing that struck me in listening back is that he really is. He just has such an unusual voice, it’s not like the singing that you hear when you think of a standard bluegrass singer—you think of them a certain way, with very strong, clear voices. However, I listen to Jerry on the CD and think, ‘This is really moving.’ He has a tremendous amount of soul in his own style. He doesn’t sound anybody else; he sounds like him. When you listen to these songs, you feel: ‘Wow, he’s really emotive. He’s really him doing the songs.’ That’s a big deal—to be yourself, to not sound like everyone else who does them.”

Although the Hart Valley Drifters proved to be as fleeting as their ephemeral band name, fixating on their brief existence misses the point. In listening to Folk Time, one comes to appreciate the spirited, rollicking energy that these neophytes brought to bear while arranging and interpreting the sounds that captivated them. As Frankel affirms, “When we were playing, we weren’t trying to become famous. We were playing the kind of music that wasn’t going to hit it big. We just loved playing that music. It was the most important thing in our lives.”

**************

In January 1961, Jerry Garcia completed a stint in the Army and returned to Northern California. Four years earlier, Wally Hedrick had introduced Garcia to the music of Big Bill Broonzy in his painting class at the San Francisco Art Institute. Garcia’s exposure to Broonzy’s expressive blues inspired the teenager to swap the accordion he received on his 15th birthday for an electric guitar that he then utilized in his high-school band, The Chords.

By the time Garcia came home in 1961, however, he was not eager to resume his efforts on the electric instrument, opting instead to focus on the fingerpicking that a friend taught him in the service. Garcia was turned off by the production sheen of the pop sound emerging from the Brill Building and sought out the authenticity he perceived in traditional folk, bluegrass and old-time music.

Garcia’s explorations during this era are captured on the aptly titled 5 LP/4 CD box set, Before the Dead. The music spans a recently unearthed duo performance with Robert Hunter at Garcia’s girlfriend Barbara “Brigid” Meier’s 16th birthday party on May 26, 1961 (with Garcia on acoustic guitar) through an appearance by the Asphalt Jungle Mountain Boys during the summer of 1964 (in which Garcia appears on banjo).

“One thing that’s incredibly fascinating to me—and has always struck me through all of this work that I’ve done on this—is that it all happened in just over three years,” explains Brian Miksis, the tape collector who set all of this in motion and served as co-producer on the project. “We’re looking at three to three and a half years when he first gets out of the Army and plays guitar, until The Warlocks were formed. A lot happened in a very short period of time, and that, to me, is the learning arc of what this set represents.”

Dennis McNally, Garcia’s friend, publicist and Grateful Dead biographer, who produced the set with Miksis, adds, “With that first tape, you’re hearing him mostly strum. And what’s striking about that tape, among other things, is the way people glued onto this 18-year-old kid. He had a presence as a performer that was way beyond his skills as a player from day one. There’s just something about his personality, and that’s why he had an audience spellbound at 18. There are also a couple of moments in there where they sing very nicely together, and the combination produces really high-quality music, even though it’s relatively simple stuff.

“Within a couple of months, at the next show, which took place at the Boar’s Head [in San Carlos, Calif.], he’s picking rather well. I mean, it’s astonishing—it really is. From all accounts of everyone who knew him at the time, Garcia woke up in the morning, picked up the guitar, and held onto it until he went to sleep at night. And, in the intervals, he played. And he grew very fast. You follow this progression, and then he gets to the banjo— to the point where you hear by the end, in 1964, a banjo player who could seriously consider going up to Bill Monroe and saying, ‘I wanna audition for you,’ although, for reasons of his own neurosis and shyness, he did not. But he was good enough to have done that. Neil Rosenberg, who was our cohort in this project and is one of the most serious bluegrass scholars in North America, would agree. In fact, Garcia’s pal Sandy Rothman was able to play with Bill Monroe for a summer, and that’s as good as it gets in the bluegrass world. Jerry could dream about that, and even if, for various reasons, he was unable to push himself forward, he did get that good.”

While Before the Dead tracks Garcia’s development, the extensive liner notes also share the stories behind the story. In addition to essays on Garcia’s musical growth with commentary and editorial contributions from Rosenberg and Rothman, Miksis pens a series of essays titled “Tales of the Tape” that share the means by which the performances were initially recorded and later acquired for the collection.

A fortuitous series of events yielded the first eight songs on Before the Dead: a performance from Meier’s birthday party by the duo that called themselves Bob and Jerry, only a few months after Garcia began to focus on the acoustic guitar and just three weeks after the pair’s public debut. Meier’s father happened to work at the Stanford Research Institute and brought home a Wollensak reel-to-reel tape recorder to capture the revels for posterity (including the sounds of presents being unwrapped and a woman’s voice interjecting, “Barbara’s mother would like to know if anyone wants any more food”).

A very short portion of this appears in Amir Bar-Lev’s documentary film Long Strange Trip. Miksis recalls, “Amir invited me to the cutting room one day, where I saw the first chapter and that’s where I saw the scene with Barbara playing the tape, and my brain went through the roof.” Miksis had initially learned of this tape’s potential existence years earlier via one of the outtakes from Blair Jackson’s biography Garcia: An American Life that Jackson posted to his website.

In order to secure the tapes for Before the Dead, Miksis turned to McNally. “I did not know that there was a recording of Bob and Jerry, that band,” McNally acknowledges. “So Brian told me about this and I said, ‘Well, that’s interesting.’ And he’s like, ‘I have no connection to Brigid and I don’t know what to do about that.’ And I said, ‘Oh, well, I do have that connection.’ We’d been friends for a while and it was certainly easy enough for me to pick up the phone and say, ‘What about this tape?’ It had never previously occurred to me to ask, ‘Oh, by the way, do you have any tapes of Jerry?’”

This account is one of many ways by which Miksis and McNally teamed up to unearth the material that appears on Before the Dead. Their collaborative efforts built on a relationship that began 10 years ago when Miksis, who had become an obsessive collector of Garcia’s early years, cold-called McNally while looking for help.

McNally remembers, “I responded positively because I regarded it as my fundamental obligation to Jerry, who made me welcome, who gave me my chance. I regard it as an absolute obligation to at least try to be responsive to everyone who reaches out to me. Sometimes that includes a lot of people with fairly strange projects. But this wasn’t all that strange. It was just, ‘I wanna know everything there possibly is to know about the bluegrass history of Jerry Garcia.’ It was a pre-Grateful Dead history and I gave him as much help as I could at the time because, over 20 years earlier, I had been doing research on that era.”

“I was a very unknown entity in any of this, other than just a fan,” Miksis adds. “And I sort of started to poke around through a few very accessible people like David Gans, who gave me some suggestions on who had done the most research on this period up to then. I was familiar with the publications that had already been done, the foremost being Dennis’ book. We spent probably close to two hours on the phone—he pulled out his raw notes and we went through just about everything. I remember there were some side notes on his papers and Dennis informed me: ‘I see there’s a name here, Ted Claire, but I don’t know why. It’s probably important.’”

Indeed, it was. Ted Claire, as it turned out, was a former Stanford student who had hosted a college radio show in the early 1960s called Folk Time that featured live acoustic music. He had recorded a number of these performances and held onto them over the years, including one from the late fall of 1962 by the Hart Valley Drifters. This group featured Garcia on banjo and guitar along with Hunter (bass), David Nelson (guitar), Ken Frankel (fiddle and banjo) and Norm Van Maastricht (dobro). The music from Folk Time—which was released as a stand-alone CD last November—is also included on Before the Dead, enriching the larger narrative.

Some of the other performances on the box set, featuring Garcia in a variety of incarnations under assorted monikers, were supplied by McNally, who copied them while researching Garcia’s early years for A Long Strange Trip: The Inside History of the Grateful Dead. Recordings of Garcia, Marshall Leicester and Hunter at the Boar’s Head from July 1961, the Black Mountain Boys at the Top of the Tangent in Palo Alto from fall 1963 and the Asphalt Jungle Mountain Boys at the Top of the Tangent from the summer of 1964 all came to the project through McNally’s reference tapes.

“As I was researching the book,” he recalls, “I would encounter these tapes and ask to borrow them to have my friends record them. I did all of this stuff and then moved on to other aspects of Grateful Dead history and, eventually, I went back and reviewed everything and put out the book. Luckily, I had held onto the proverbial shoebox that I put everything in.”

Miksis, who makes his living as a location sound mixer for TV and film, has started filling a shoebox of his own—his work on this era has inspired him to initiate a documentary-film project that will explore the folk revival in the Bay Area. “Being a sound man in the film business, it seemed like the natural thing to start trying to develop the idea for a doc film that covers not only Jerry, but all of these other guys who deserved the same honor to have their story be told,” he says. “How did the Weavers lead to Jefferson Airplane? Believe it or not, there’s a pretty direct link that I think a lot of people miss. Jerry is only a character in the film that I want to make. I feel like there’s a much deeper story as it pertains to the Bay Area and what makes it different from what was happening on the East Coast in Greenwich Village and Cambridge.”

Jerry Garcia would have celebrated his 75th birthday this August and Before the Dead is a fitting way to mark this milestone. Garcia’s acoustic interlude set him on a course that would help define his approach and aesthetic even after he returned to the electric guitar.

“While some of this music has been available to a few collectors, there are two big distinctions,” Miksis remarks. “One of them is you’ve never heard them in this quality because I did the work of finding a lot of the master tapes, which nobody else had bothered to do. But beyond that, when I first was getting these tapes as really crappy cassettes, nobody knew what this material was. Nobody knew its function in the larger mind of Garcia—how it played its role and helped form what we would later be listening to. The most important thing about this box is that it gives context to all this material. Even Deadheads, who only tangentially might be into bluegrass and folk music, might have a strong interest in a little bit more of the psyche of Garcia in those early formative years.”