The Bottom

The album opens with a laugh, but there is no joy in it. The singer sounds as if he’s mocking the very idea of laughter. In a world as diseased and artificial and pathetic as this one, how could anyone laugh? You’d have to be stupid. You’d have to be a fool. Welcome to The Top.

In 1984, during what would prove to be a career of transitions, the Cure released what is probably their most transitional album. But unlike most transitional albums, The Top bears little resemblance to what would come afterwards. The Top looks backwards to Pornography but looks forward only to oblivion. Pornography is usually considered The Cure’s bleakest moment, but it has an anger and desperation to it that’s missing here. Where that album opens with the crushing line “It doesn’t matter if we all die,” the stories on The Top could be reduced to “It doesn’t matter if we all live.” There is no catharsis here, no possibility of escape. Everywhere Robert Smith looks, he sees a wall, or a mirror, but never a door, not even a window. Even the album’s jauntiest song, The Caterpillar, tells a story of hibernation, a temporary death that must happen in order for the subject to become beautiful and reach its fullest potential. And as he sings, Smith sounds like a man who doesn’t believe he will be around to see it happen.

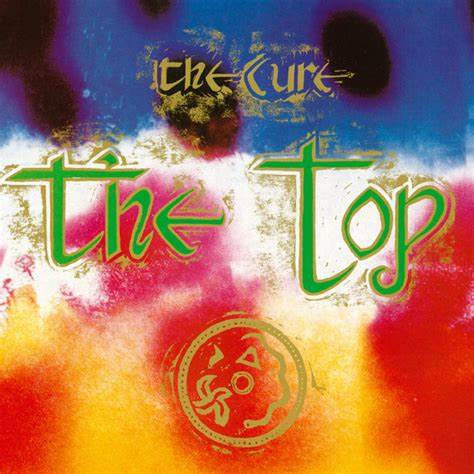

Emotionally, The Top runs back and forth between depression and a bleak scattershot nihilism. Trapped in an endless maddening loop, everything Smith sees is filtered through a cynical lens, a cynicism that has even infected his music. According to the singer, the previous year’s single, The Lovecats, was “composed drunk, video filmed drunk, promotion made drunk. It was a joke.” The cover is a psychedelic blur. Nothing is focused. You can’t make out anything clearly. It is, shall we say, appropriate for the material.

The Top is also The Cure’s most decadent album. The album is crawling with sex, but the sex here isn’t just unfulfilling, it’s unfeeling. No matter how hard Smith pushes the act into extremes—and he takes it to some very extreme places—he still isn’t able to feel anything. In Shake Dog Shake, hair is pulled, skin is scraped with razor blades, and Smith is hit by his lover. Give Me It sees cats being sliced open and eaten. There is thick blood, choking, and needles that penetrate the side of the narrator’s body. All of the acts are meaningless, all of them useless. The graphic sexual imagery on The Top isn’t that different from songs Smith had written before, or songs he would write afterwards, but the way he delivers the lines here is so blank, so far removed from any emotion, that they feel somehow more disturbing. It probably doesn’t help that, with the exception of ‘Shake Dog Shake’ and ‘The Caterpillar’, the rest of the songs have a melodic aimlessness to them as well—an unfinished quality that suggests Smith can no longer find anything of value in his music. It’s almost like he couldn’t be bothered to lend any kind of focus, or didn’t have the energy to try, and so most of the album goes by as a sort of formless sludge. Everything feels random, and slightly disturbing, and the disturbing parts become more disturbing because of the randomness. It is, to put it quite simply, a major bummer. The Top is the sound of a circus populated with dead animals, tightrope walkers who slip and crash to their death, and clowns that haven’t made an audience laugh in months.

It doesn’t make for a satisfying listen, but perversely, that is what makes the album worth listening to. In a career of albums that could be—and have been—called depressing, The Top is The Cure’s most truly depressing album, as it is a very real, very accurate depiction of the depressed state. It may not be useful as art, but it has a lot to teach us if we’re willing to listen to it in the context of Smith’s larger body of work.

We’re conditioned to view depression as something bad, some sort of faulty wiring in our neurological system, but depression can also be a necessary, even vital, part of processing trauma and pain. But instead of seeing depression as an inconvenient obstacle that we need to get rid of as quickly as possible, it’s better to see the value in it. Depression is the body’s way of forcing us to stop. It is trying to get our attention. It is trying to tell us something. It is a necessary rest. It’s more helpful, and more accurate, to see hibernation as a kind of enforced hibernation period. I doubt Robert Smith saw it this way at the time, but a depressed person—someone who desires to sleep for long periods of time, who is barely able to function, who would prefer to spend most of their day in bed—has a lot in common with a caterpillar in its metamorphic state. After all, the chrysalis, or the cocoon, is not unlike the depressed person’s bed.

Consider this description of a caterpillar’s metamorphosis from Scientific American, which sounds like lyrics Smith could have sang on The Top:

First, the caterpillar digests itself, releasing enzymes to dissolve all of its tissues. If you were to cut open a cocoon or chrysalis at just the right time, caterpillar soup would ooze out.

The creature—no longer caterpillar, not yet butterfly—can’t begin assembling itself into its new form until it’s finished dissolving, until it becomes nothing. The Top can be heard as Smith in a state of dissolution, the singer as caterpillar soup. In this light, the song The Caterpillar takes on a deeper resonance, it becomes a promise that can be heard as a glimmer of hope amidst an album of despondency. The caterpillar in the song isn’t going to be a caterpillar forever. Because there is only one law of nature: everything changes.

Depression is the worst kind of liar—a liar who sounds like they’re telling a deep and profound truth. The biggest lie depression tells us is when it tells us we will always feel like this, that the dark cloud will never go away and we are powerless to resist it. But if we are patient, if we allow ourselves to feel whatever needs to be felt, we will eventually find ourselves taking slow, tentative steps away from the darkness. Because everything changes. That is the tragedy of our existence, but it is also our salvation.

One of the last lines on the album says, “The top is the place where nobody goes,” and yet a year later, The Cure would release The Head on the Door. The album would be Smith’s most focused, accessible work yet, and would provide him his first gold albums in the UK and the US. Within five years he would see albums reach #1 in the former country and #2 in the US. The top may be a place where nobody goes, but Smith found a way to get there, and in the process he created his most enduring body of work. As for the bottom, that’s a place where everyone goes. Some people never make it out. The Top is a perfect companion when you’re at the bottom. It can be a source of comfort, and it can reassure you that it’s worth sticking around to find out what happens next.

________https://youtu.be/bJUHp7wrC1o

[embedded content]

Scott Creney is the co-author of The Story of the B-52s: Neon Side of Town, out this spring on Palgrave Macmillan. He recently moved to the New York City area with his family and is worried they won’t be able to make ends meet. Please send money and non-perishable food.