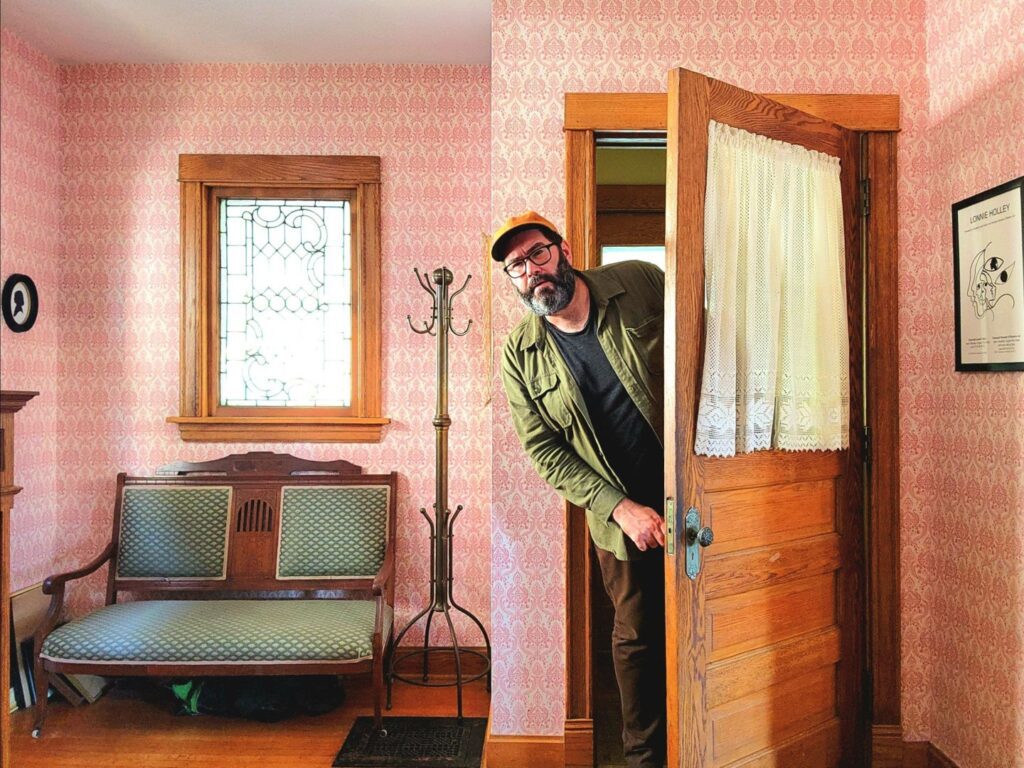

Owen Ashworth. Photo by artist

Owen Ashworth didn’t want to make Horrible Occurrences. He’d written “The Year I Lived in Richmond,” a true story about a serial killer dying at the knife of a potential fifth victim, and he hoped that would be the end of it. But the tragedies kept flowing. A melody or chord progression would catch his ear, and he’d free-associate lyrics, following his subconscious until the sounds formed words and the words invoked an image. Over and over again, those images were snapshots of disasters.

“The songs felt a little cursed,” he says now from the basement of his home in the Chicago suburbs. “I kept putting them down and trying to write a different kind of record, but I kept getting drawn back to these stories.” If he was going to move on with his life, he needed to follow the road to its end. He needed to invent a place where all of these horrors could live together and interact with each other. “These songs are going to be in the back of my head,” he thought, “until I root them out, release them, and process the whole thing.”

Over the past quarter-century, Ashworth has become a quiet titan of indie music. The label he founded and now considers a full-time job, Orindal Records, helped launch artists like Wednesday, Julie Byrne, and Dear Nora. The 26-track tribute to his work as Casiotone for the Painfully Alone and Advance Base, released in 2022, is proof of his immutable influence on modern indie songwriting. But it’s also proof of his unique approach to making music; no one else quite captures Ashworth’s peculiar loneliness.

His songs sound like little lullabies, simple melodies sung in a languorous and intimate baritone, usually over little more than an electric piano repeating hypnotic chords. His lyrics are stark vignettes about ordinary people navigating quiet hardships, heartbreaks, and happinesses, everyday dramas rendered cinematic by Ashworth’s carefully deployed details. There is something unmistakably wintry about Ashworths music, between the warmth in his voice and the loneliness his protagonists wrestle with, and it’s little wonder that he’s written multiple albums’ worth of affecting Christmas songs.

Horrible Occurrences goes far beyond that quiet melancholy, though. The opening song’s protagonist leaves town after killing her attacker, but Ashworth’s focus stays on the fictional town of Richmond, with its deaths and disappearances, catastrophes and ghosts. A little girl confronts her alcoholic father; a wannabe daredevil kid shatters his spine; a young man drives off to a lighthouse in his pickup truck one winter and never comes back. In an effort to capture the essence of Ashworth’s live performances, these disasters all play out over the sparsest arrangements imaginable, and that only heightens the sense of terror. There are no distractions. The listener has no way out of Richmond. But even in the cold, Ashworth is always present, a warm and empathetic voice above the silent snow.

If I were visiting the fictional town of Richmond for the first time, how would you describe it to me?

You see a lot of dried up industry and you see some faded glory and, but also new industry and new construction — the erasing of a place’s history as it starts to just look more like anywhere else. I think a lot about the mix between old architecture and new architecture. I imagine a lot of brick in Richmond, a lot of rust, a lot of overgrowth in abandoned buildings.

You played these songs for the first time, long before you recorded them, in towns that look just like that. Were you drawing inspiration from those places as you went?

One thing I really enjoy about being on tour is just the experience of being a stranger, just having fresh encounters with everyone. It makes me more conscious of myself and aware of first impressions. I think an important part of my identity is presenting myself as a stranger. It’s a really stark contrast from going through the shows where there are people anticipating my arrival. I think it reminds me of who I am. I think it helps me balance my ego.

But it’s work. I’m thinking all day long about the show that night and what songs I want to play. Each tour feels like an ongoing project where each night is like another draft. Each night is a chance to refine the performance and try different songs. I love that process. I love having this ritual that I’m repeating every night, making small adjustments and reacting to the audience or the venue, reacting to whatever happened to that day. I was really taking audience reactions as my editor for a lot of these songs. Tours were crucial to where the songs ended up.

I think the emotional stakes for my songwriting are much higher. I feel so invested in these songs.

Was there a moment in that audience reaction that you found particularly surprising?

There’s a song on the record called “The Tooth Fairy” that I found just really upsets people. I’ve been thinking about this a lot. I would notice people leaving the shows after that song. Maybe they’re just like, “Fuck this. This is not what I came out for tonight.” Or maybe they need a minute, or maybe people are just stepping just cause it’s an emotionally heavy song, and it takes people back a little bit because there’s a lot of apprehension in what could happen in the story. But I see that song getting in people’s heads more.

You know, there are songs about murder on that record that seem to upset people less than “The Tooth Fairy.” Gauging people’s engagement with the lyrics in real time informed not only the sequencing of the record, but what happens in the song and the pacing of the songs in the presentation. I really valued having real-time reactions and sensing the temperature in the room change based on certain lines. But “Tooth Fairy” really fucked people up. That was surprising.

The one that fucked me up the most was “Brian’s Golden Hour.” It leaves you hanging.

Sometimes these songs feel really sadistic to drop on people, but I hope people recognize that for my part, there’s so much compassion going on in [them]. And these are just representations of my anxiety. So I hope the feeling people get from the songs is like, “Yeah, me too.” I hope people can feel the care and gentleness.

You do always seem to empathize with these characters. How do you get into a character’s head?

Well, I feel like I’m everybody in all the songs. The way the songs usually start, they’re very musically repetitive and hypnotic. There’s a lulling, meditative quality to the way I start making music. I’ll have some basic musical elements, a chord progression or a melody or a drone that catches my ear, and I have some kind of emotional reaction to it. And then I will just play with that sound free-associate lyrics for a long time. I’m trying to follow my subconscious. Where is that feeling coming from and what is it about? I’m chasing down those feelings. Sometimes the sound will conjure a certain image. Why that image? What is happening in that location? What is happening with that person? I’ve been trying to just get out of my way with songwriting more consciously.

Once I have a handful of these songs, I start looking for the common elements. What are the images? What are the characters? What are the places that are these songs have in common? I’m trying to just build a story and make connections between them, build out a world from there. But every time I make a record, it feels like I’m populating a little town, figuring out who these people’s neighbors are, who are they reacting to. What are the reverberations of these stories in a greater community, down a family line, or just in the history of a place?

Do you think that “The Year I Lived in Richmond” opened the floodgates of anxiety? Do you think, without that song, you would have written such an anxious record?

I don’t know. Originally, I used the name of the real place, but that didn’t feel right. I didn’t want to make the people who actually live in this place have dark feelings about where they live, and I don’t want someone, and I don’t want anyone to think that I have a dark opinion of a particular location. Bad things can happen anywhere, and that was kind of the point.

Once I decided that this song didn’t happen anywhere, I had this idea of a fictional place where bad memories had happened to someone and they left like that. Every Advance Base record has started with a departure or an absence. It’s not something that I did consciously, but looking back as I was putting this record together, I realized that the first song on every record is somebody leaving, and then somebody else processing that absence. On “The Year I Lived in Richmond,” there’s a departure, and that was a really good place to start the record. So, what else can happen in this town? What is the history of this place? Who are the other people who live there? I wanted just that true crime story to be echoing in the background through all of these songs. Like, you live in a place where sometimes terrible things happen, and we all continue to reckon with that trauma.

Sometimes these songs feel really sadistic to drop on people, but I hope people recognize that for my part, there’s so much compassion going on in [them]

Do you find it therapeutic to write those stories?

The therapeutic part for me was writing the song and feeling what I wanted to say with these songs. I process whatever feelings I have through the song. Playing them on tour — the transmission is completed. I carefully spent a lot of time figuring out exactly what I wanted to say. I delivered it to people. It was received. I feel heard. Great. I think the part that doesn’t feel therapeutic is to make a record and to continue to talk about it for months, and I’ll continue to play these songs until it drives me crazy. I feel like I’ve done the therapeutic work already, and this is what’s left over.

That has been a big change in my process. I think the emotional stakes for my songwriting are much higher. I feel so invested in these songs. I’m putting a lot into them to the point where I these songs have stopped to feel useful for me. What keeps me going with it is that I recognize they have use for other people. And as long as there are people coming to hear the songs, I feel an obligation to perform them to the people who want to hear them. But the therapeutic part for myself is done. I don’t know how healthy it is from here on out.

A lot of songwriters who have been writing, performing, and touring for as long as you have can get cynical as years go by, for very good reason. And obviously the last 30 years that you’ve been doing this, the industry has changed massively. I wonder if running Orindal has maybe protected you from that cynicism a bit.

There are aspects of running a label that have certainly honed my cynicism. There’s a lot about the music business that I find really repellent, and that’s the part that feels like work. It’s just the commerce of the whole thing. But helping someone make their beautiful record, making it look and it sounds as good as possible, helping someone to realize the thing they had in their head — that’s the most satisfying thing for me.

Before I let you go, it’s December, and I have to ask about Christmas. What is it that draws you to writing about that time of year?

I have my religious trauma from youth and going to church when I did not want to be at church. There are just so many complicated feelings around the holiday. It just seems like the intersection of so many potent aspects of life: family dynamics, organized religion, the harsh reality of commerce. But there’s also beautiful history. The most basic pagan tradition, you light up the darkness and there’s warmth in the cold. I love seeing Christmas lights on a dark night; there’s just something so primal and basic about it. Writing about Christmas is just a shortcut to so many really heavy emotional centers for so many people.

My mom would sing in the choir at the Episcopal Church when I was a kid, and I have so many sense memories attached that: the smell, the sound, the very specific lighting situation. There’s so much warmth in Christmas, but so many dark feelings have come right along with it for me. I just kept being drawn to it. Every year, Christmas is back, and I’m reckoning with it in a different way again.