“My relationship to the Grateful Dead was fairly limited until I started getting tapes of their music when I was about 17,” acknowledges artist and author Mark A. Rodriguez. “I only had three Grateful Dead albums, so I wasn’t a completist in terms of their studio discography. I had Anthem of the Sun, Wake of the Flood and Blues for Allah, which are still some of my favorite albums. But I developed a relationship with the Dead through their live recordings.”

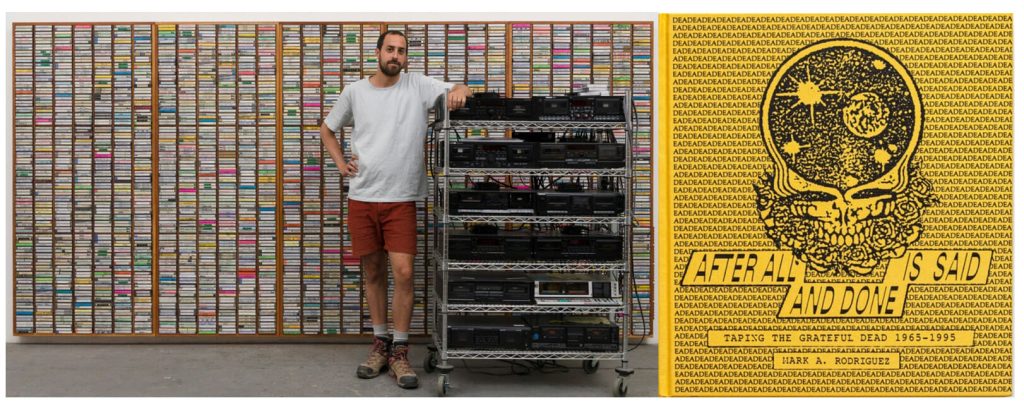

This seems altogether apt, as Rodriguez later gained renown for a series of sculptures based around Grateful Dead tape trading. That, in turn, led to his new book, After All Is Said and Done: Taping the Grateful Dead, 1965-1995. The first section of the hefty tome presents images of the colorful J-cards that accompanied Dead tapes. Then the work delves deep into the origins of the Dead taping section and tape-trading community through a series of interviews, images and documents drawn from the official Grateful Dead Archive at UC Santa Cruz— including some revelatory correspondence and official Minutes of the Meetings held by the group.

Rodriguez grew up in the Chicago area, and after he received his initial Dead tapes in 1998, he embarked on some early fact-finding missions that anticipated his efforts two decades later.

“I used to go to the Evanston Public Library, which is near the Northwestern campus and a bike ride from my house,” he recalls. “I would usually be in the stacks, looking at whatever data I could get, as far as my new musical interests were concerned. I wasn’t going deep into microfiche. It was mostly history books or magazine articles that I would gobble up.”

What are the origins of your Grateful Dead sculpture project?

It was prompted by a conversation I had with a fellow artist, Matt Siegle. We were working together at another artist’s studio as artist assistants, and we had lots of time on our hands because, as an artist’s assistant, sometimes you’re doing really nitpicky things. While we were talking, somehow we figured out that we both followed Phish back in the day. Then we started talking about Dead tapes and if there was a possibility of using that as an artistic medium.

As a result of that conversation, I decided to see if I could locate some tapes because I was in LA at that point, and my tapes were in Chicago. It wasn’t like my parents were going to send them to me, and I didn’t really want that.

So I posted a Craigslist ad asking if anyone had any Dead tapes they wanted to get rid of. That was in 2010, so we’re talking about a time period when CD-Rs had pretty much replaced tapes and the Internet Archive had already started amassing sound sources. It was a ripe time to step into this, and a gentleman from West Hollywood ended up replying to my ad and said, “I’ve got a hundred tapes; I’d be happy to give them to you.”

I met him in the lobby of his apartment, talked to him for a little bit and walked away with a hundred tapes. Then I sat with the tapes for a while, organized them in chronological order and got a tape deck to listen to what I had. I spent a little bit of time being with them and seeing what kind of phenomenological effect they had on me as objects. I was taking more of a critical and analytical approach to them rather than just being like, “Cool, I’ll play all these things, listen to the data and that’ll be it.”

I was trying to figure out if I could work with this as a medium. Eventually, I scanned in all of the J-cards and then I started to think about how to accumulate more tapes.

What I ended up doing was collecting tapes all across the country through Craigslist. I would go to any state that had a Grateful Dead kind of headiness to it, like California, New York and Massachusetts, as well as other spots like Montana, Oregon and Washington. I was checking Craigslist in every city that I could, putting in Grateful Dead keywords and seeing if anyone was giving away tapes.

This was a moment where people just didn’t really know what to do with this dead medium, not to make a pun, but they also didn’t want to throw them out. So it was kind of this funny dilemma reinforcing that these tapes could be charged spiritual objects that had individual histories assigned to them. They had a uniqueness that produced guilt in the owner if they chose to just throw them in the trash.

So I was able to get collections from all over the United States through that process and I quickly accumulated a few thousand tapes within a year’s time. During this era, something that always stuck in my mind was this website called One Red Paper Clip. It detailed the attempt of an individual to trade a red paper clip up to a house. So that always stuck in my head—“If this guy can trade a paper clip to a house, I can use the internet to get every single Grateful Dead show that has been recorded and is available on audio cassettes.”

I used Tumblr as the platform to attempt that kind of appeal. I decided to start posting J-cards from the day a certain concert happened. So on Dec. 28, 2011, I would post the J-card from Dec. 28, 1978. Finally, around 2015, I was like, “I have a lot of tapes. I need to s tart working on the art project.”

I had already spent a lot of time sifting in the stew of Grateful Dead tapes, but now I developed a way to work with them in a medium that also worked with my artistic process. It deals with systems, repetition, ubiquity, Americana and making art that removes my hand from the process so that it plays more into that semblance of an authorless kind of art.

Around 2015, I started dubbing tapes from what’s considered 1st Gen, which is the first sculpture in the series of tape sculptures that I’ve made with the tapes. I dubbed 1,700 tapes from 1st Gen and those 1,700 tapes would be included in 2nd Gen—along with the doubles that I had accumulated—so that both 1st Gen and 2nd Gen were similar to each other. Then I could move on down the line to further create that series.

At what point did you begin exhibiting?

1st Gen was shown in 2016 at a gallery named Park View in Los Angeles. Then 2nd Gen was shown at NADA Miami, which is an art fair. 3rd and 4th Gen were shown at the Frieze art fair in Los Angeles in 2019. At that point, it went into what is considered in the art world to be a pre-order. It started to be sold for private collections. So those first four versions were all shown, and then 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th and 9th have not been shown publicly.

Would it be possible for someone to remove the tapes and play them if they so desired?

They can play them but, as my intent comes into it, some of those tapes are not going to have the information in the most listenable condition. I will say further that it is my intent for there to be a mix in quality as part of what I’m trying to propose with this series of sculptures.

In general, my intent is for the person who purchases the sculpture—and wants to live with it—to understand that it’s more than just the wall of tapes. It’s also my artistic gesture, which is pointing to the phenomenon humans participate in by wanting to collect, accumulate and complete a history. In this sense, it’s a particular history that is quite unique in that it’s probably the most complete evidence of an ensemble band’s artistic output. You can basically collect their complete artistic output, which is quite unique. But what I’m also doing is muddling with that and making it incomplete by lowering the sound quality of these tapes, as I dub them to create the series.

First and foremost, it’s my hope that an art collector— or someone else who collects the piece—has some understanding of that. If they do want to play the tapes, they certainly are welcome to, but I also know that a lot of the people collecting don’t necessarily have tape decks and this isn’t really an interest of theirs.

When I exhibited, people often asked, “You have tapes in there that actually work? I thought it was just tape cases in there.” They’re always surprised that I went through the trouble of actually putting in tapes. That’s when I’ll explain that it’s all part of this endurance process, whereby I’m trying to manually override the completeness of the sound and the history as a part of my artistic intent.

So I could have done it in an easier fashion and pumped these things out. But for me, part of the pleasure is the pain of the endurance—of going through the whole sequence of selecting tapes, getting tapes, dubbing tapes and going through the whole rigmarole.

In the foreword to your book, Trixie Garcia mentions that you were the first person to approach her regarding her dad’s digital art. What was the nature of your inquiry?

At the time I got in contact with her, I was working on another book with two other people—Matt Siegle, who I had mentioned earlier, and a woman named Elizabeth Cline. We were all Deadheads in the art world in LA. During 2010-13, there was a funny phenomenon where we felt like we were closeted Deadheads in relation to an art world that wouldn’t take the subject matter seriously.

If I were talking to someone at an opening and they asked me what I was working on, and I would say, “I’m trying to collect every Grateful Dead show on tape,” that would be kind of laughable. They wouldn’t say, “Oh, that’s really interesting, why?” It would be, “You’re doing that? That’s funny.”

So during that time period, we kind of got together and found camaraderie around our fandom of the Grateful Dead. But we also were like, “How can we engage the art world to approach the Grateful Dead in more of an academic and critical way?” So we made this book that asked artists, writers, poets and different creative types how they would respond to the prompt of the Grateful Dead. It’s called If the Head Fits, Wear It and it’s mostly those types of responses.

As an editor, when I came upon Jerry’s digital art output, I thought it was really interesting. It was kind of crude but experimental because he was working with an Apple IIe or something like that which had fairly early graphic arts capabilities. I was fascinated by that, and we engaged a writer and art critic, Eli Diner, to write about it. I initially got in contact with Trixie, who helped me get examples to print in the book, which eventually was published in 2017.

What prompted the decision to create this new book?

Did you always intend to include all the archival materials in addition to displaying the J-cards? My original thought was that I wanted to make a book from all the J-cards I had been scanning for that Tumblr page. I was sitting on all this information because I had made the decision for the sculpture only to show the spine of the J-cards. There was a lot that couldn’t be seen, like the setlists and any graphic design that wasn’t visible on the spine.

Part of it was this weird, guilty feeling because I was working with these charged sacred objects that had more life than I could show in the sculptures I was making. I thought, “If I could pitch it as a coffee table book about J-cards, then that would ease the sense that I was doing a disservice to what I had amassed with the collection of tapes.”

That was the start of my thinking about it. I pitched the book as “the art of the J-card,” but I also proposed a history of taping, although that was very vague because I had never pitched a book to a publisher before.

It turned out that Anthology Editions was into it but then there was a three-year process of trying to get Grateful Dead licensing on board so that Anthology could use the trademarks of the Steal Your Face and the Dead Bear for advertising purposes.

With the previous book that I mentioned, we had been in contact with Rhino and it was a seemingly easy, although very long, process to get permission from them. We did this small publishing run—it was maybe a hundred books—and they allowed us to use the licensing agreement for academic purposes, which was generous.

In the beginning, when I was talking with Anthology, I was like, “I just printed this book so it shouldn’t really be a problem to get licensing.” But we were denied the first time. Then over the span of three years, I tried to make supportive connections within the music world, which eventually happened with Mark Pinkus and Bernie Cahill.

By the time I finally signed the contract with Anthology in late January 2020, I had been thinking a lot about how to format the book and what I wanted out of it. I decided that while making a book of J-cards would have been fine, I wanted to do something a little more exciting. I wanted to provide new information that hadn’t been published. I also wanted to talk to people internal to the organization of the Grateful Dead. On top of that, I was thinking about the art project and providing context as to why these J-cards exist in this format.

In February, I traveled to the Santa Cruz archive, thinking that I would look up all that I could find in the database about taping and the tapers section. I lost one day of research to a student strike that shut down the entire school, so I only had one day where I feverishly went through every single file I could. Then when the pandemic started, I had a lot of time to analyze everything.

Before I visited the archive, I interviewed David Lemieux with the thought that I would have extended interviews with all these people and then connect the dots with the documents that I located. As I started the interviews, I also began growing my contact list, and people like Stu Nixon or David Gans would lead me to other people.

So everything kind of grew. I ended up with over a thousand pages worth of interviews to whittle down. I also had the business minutes, which for me was this prize that I wanted other people to see. I knew it was something special that not everyone has access to, in terms of being able to visit the archive. There were a lot of documents that I wanted to have an excuse to be able to put in print. So the final section of the book was my way of finding a reason to do that and provide auxiliary information through interviews with the people who might have written a memo or might be mentioned in a particular section of a business minute item.

Can you talk about the graphic design choice for that last section, which feels a bit like a zine?

The whole aesthetic was based off a couple of key graphic arts entities. We started with Unbroken Chain, where the first issues are basically a broadsheet with a bunch of data crunched in between graphics. It looked cool, but it was a little too intense. So we tried to distill that a little bit more so that the sentiment was there and it gave us the ability to insert all these Relix interviews and Dupree’s Diamond News interviews. Most all the auxiliary interview information and auxiliary articles are inserted in a way where they correlate to what’s being talked about in the interviews, but the design is made in such a way that you can see the separation. So as a reader, it’s not like, “See item one, see item two” where it’s treated like a footnote. Instead, it’s just there. I was trying not to create too much pressure or preciousness to everything so that you don’t feel intimidated by it.

The people at Anthology weren’t hardcore Deadheads, so I was advocating for taking up page space with these things that might seem nerdy and minuscule. But when it came time to display the minutes, I wanted to show the whole page—so that you’re not only able to see what I’m trying to emphasize, which is circled, but all of this other stuff they were dealing with as a band and a group of employees. It’s not necessarily just about putting on the concert, playing the music and being done with it. There are lawsuits and products and sound systems and technology. It was important to me to be able to figure out a way to display the whole page or pages, so that a reader could assess how valuable or interesting that information was.

This was also true of the interviews, where I could have cut them up so that each subject is talking about the same thing as the other interviewees. That would have removed the context of the conversations and removed me as the author of the conversations. But instead of that, I thought it was more powerful to extend them.

For me, that section is a throwback to how I found out about the Dead going back to my days in the library. I thought about this while I was making that section and deciding how to display the information. Ultimately, I wanted to present it in a context where you could turn to any page and come away with something that could be connected to other things if you turned the page and kept going. But if you just opened to a single page, you’d also discover something that was cool in its own right.

Circling back to where we started, how close are you to amassing tapes of every Dead show? Can people track your progress and contribute?

I’m about 160 tapes away, but they’re not heavily traded shows by any means. I feel like I may have reached the end point of accessibility and that those tapes reside in the collections of old-school tapers. They likely don’t know about the project, don’t care about it, won’t allow those tapes to see the light of day or some combination of all three. I have cross-referenced different sources to confirm that it is theoretically possible to access those shows as tapes.

I’ve been offered magic two-terabyte hard drives from people who are like, “Why are you doing this? I have every show on hard disk. Why don’t you take that?” However, I’ve always denied that because I think part of what makes this meaningful is the endurance of actually finding these on tape. That rule set also doesn’t allow me to dub off of Archive.org.

The list is always on my Instagram, @Dead_Tape_Collector. It’s in bright yellow so that people can find it easily. But I’m at a stalemate at this point. I’ve tried my darnedest within my powers to try and find them. As visibility grows for my project, though, I’ll sometimes ask myself: “I wonder if these tapes are finally going to pop up?”