Xiaohongshu

You’ve likely already come across the name: Xiaohongshu, or more commonly known as Red Note, the Chinese social media platform that TikTok users are now flocking to in droves ahead of the app’s potential ban on January 19. In the span of a few days since the Supreme Court began proceedings on whether TikTok’s Chinese ties pose a national security threat, Xiaohongshu skyrocketed to No. 1 on the Apple App Store — an irony that perhaps boils down to TikTok’s penchant for appreciating a good joke. U.S. news media rushed to explain what Red Note is as TikTok videos urging fellow creators to migrate accrued thousands of views. But nobody could’ve really predicted what would happen next: thousands of American and Chinese netizens digitally meeting each other for the first time under unprecedented circumstances.

Xiaohongshu launched in 2013 primarily as a social e-commerce platform and has largely hosted online shopping, beauty, and styling content, according to Jing Daily. (Functionally, there isn’t really an American equivalent but consider it a mix of TikTok, Instagram, and Reddit.) That’s undeniably changed.

As Chinese content creators tell it, many of them woke up the morning of January 14, to find their Red Note explore page filled with the faces of “老外” (lao wai) or foreigners. “Did I click on the wrong app?,” one Chinese user wondered in a video. American TikTok transferees (who quickly acquired the label of “TikTok refugees”) made videos cautiously introducing themselves to their new Chinese audience, and Chinese content creators welcomed them in kind with their own unofficial “guides” to the app and beginner Mandarin lessons.

This lady was so overwhelmed with joy to be able to communicate with Chinese people in Chinese on XiaoHongShu. This is beautiful y’all 🤝💕✌️ pic.twitter.com/pAnIi1FdMU

— N.E.Destruction (@plantmoretreez) January 15, 2025

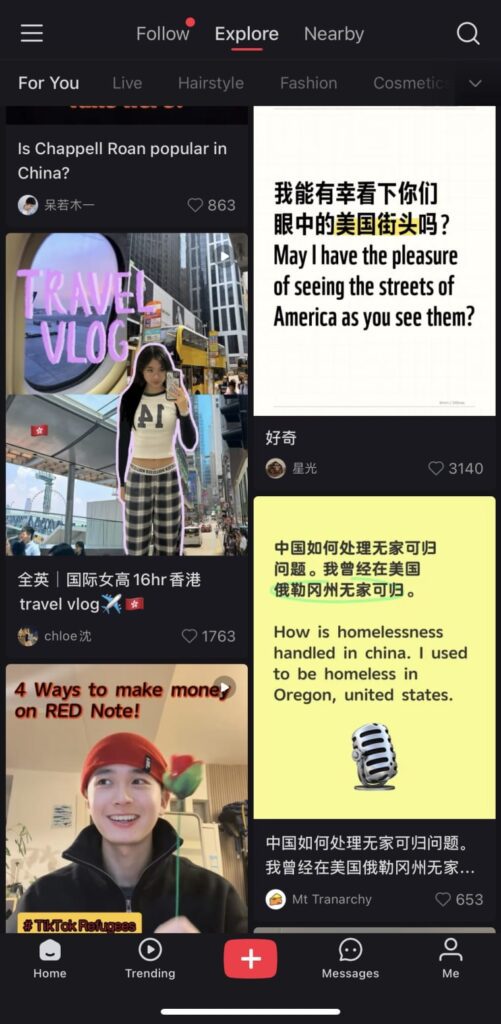

But in the last 24 hours, things have progressively become more interesting, strange, and hilarious. A scroll through my Xiaohongshu explore page brings across posts ranging from the innocently mundane — “I want to see street pictures in the US” and “what are your thoughts about americans moving to this app?” — to the more provocative: “Do you think USA will ever have Worker led revolution?” Certain U.S. users have begun a sort of self-policing as they fear their presence may represent a sort of colonization, urging one another to translate their comments and videos into Mandarin. American users delighted at discovering that Chinese “brainrot” does exist. And Chinese users, alarmed at the type of content American TikTok users are used to posting, released guides to not post anything relating to religion, gambling, or politics (though their interpretation of the latter seems to be quite loose given the app’s strong Luigi Mangione fandom).

Screenshots from the author’s Xiaohongshu explore page.

This bizarre culture clash has exposed the limits of the internet’s reach, something most American users assume doesn’t exist. China’s infamous Great Firewall, though easy to bypass with VPNs and other modern tech, has largely been successful at sequestering their country’s users inside their own social ecosystems. In America, apps like TikTok and Instagram utilize sophisticated algorithms to largely ensure that any content one is exposed to is filtered through parameters like geography, age, “interests” and more. In my personal experience, travelling abroad was the only way for me to actually tap into “French TikTok,” “German TikTok,” etc. Perhaps Xiaohongshu has similar filters in place, but it seems unlikely considering the app was made primarily for a Chinese audience. Thanks to a userbase almost exclusively (for the moment) from mainland China, Xiaohongshu actually feels like a first encounter for many U.S. and Chinese netizens to truly meet one another on an equal digital playing field — a real wild, wild west for international discovery and exchange.

Xiaohongshu’s new arrivals have already led to shifting perspectives. Some American users, for their part, are realizing that Chinese netizens are more or less just like them — an epiphany that seems elementary but also reflects a powerful tearing down of decades of socio-political messaging. “They want people from the two strongest countries to hate each other but we have learned we have a lot in common,” commented one American user on the app. Meanwhile, Chinese users, are getting the rundown on every facet of daily life stateside, from ice finishing in Minnesota to American memes.

For now the cultural exchange has generally stayed along innocent lines. In the wake of the TikTok exodus, Xiaohongshu, which only has one version of the app, is reportedly developing more capabilities to support its English-speaking user base. But given how things are going, with countless American users claiming they’re going to start “learning mandarin,” they may not have to — which I’m sure will be ideal for everyone’s personal Chinese spy.