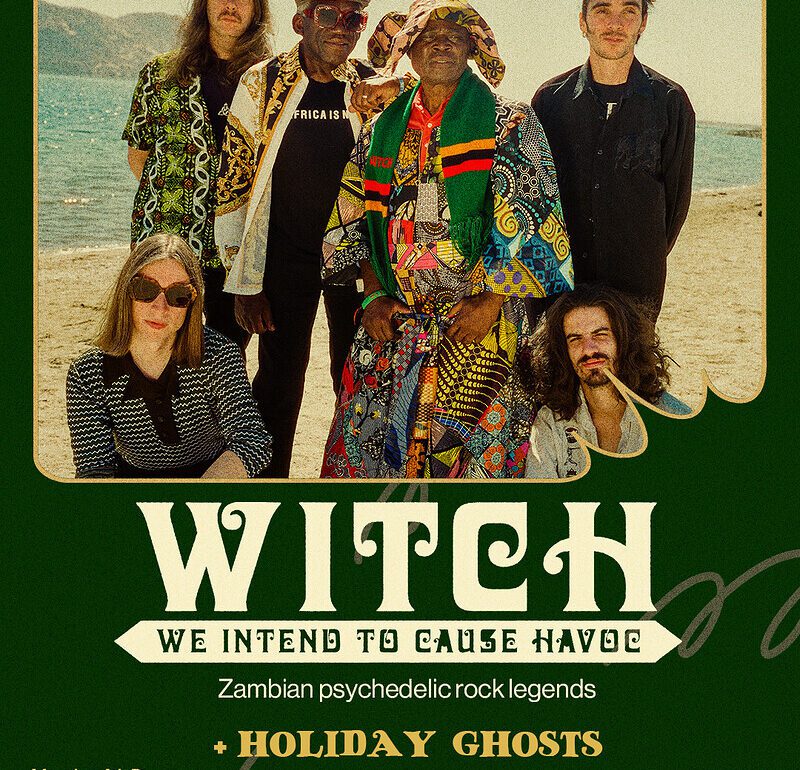

Widely regarded in the ‘70s as Zambia’s premier musical act, W.I.T.C.H. return to the UK this winter to promote their eighth studio album, Zango. This is their first new release in thirty- nine years; a potent blend of psychedelic rock, blues and funk melded deftly with traditional African instrumentation. Spearheaded by founding member Emanyeo ‘Jagari’ Chanda, the last decade sees the Zamrock pioneers enter a new incarnation, with the backline largely provided by a younger crowd of touring musicians. The songs are reinvigorated in a contemporary milieu, whilst homage is paid to the enduring legacy of the genre.

As the concourse fills, it hums with a nervous enthusiasm. Tonight’s show is sold out; a triumphant culmination of a lengthy eighteen-date EU/UK tour, beginning nearly a month ago in Utrecht, the Netherlands. The venue’s extensive lighting rig soaks the room in a fruit- salad smog. A disco ball, hanging from the corrugated ceiling, sends spears of light into every corner. There is a tangible energy as the band sway into position, the cry of guitar rising like hot air under the thunder-crack of a kick drum.

“I’ve only been to Bristol in my dreams”, says seventy-one-year-old Jagari, as he bobs towards his microphone. He is adorned in a chicken mask and a DIY-painted leather jacket.

The band was revived in 2012 with the help of documentary filmmaker Gio Arlotta,

accompanied by Dutch musicians Jacco Gardner and Nic Mauskovic who form part of the touring outfit. When Arlotta found Chanda in 2010, he was mining gemstones on the Congo border, having not performed live music in decades. Now driving his flag into an independent arts centre in Bristol, the veteran moves hypnotically, body convulsing as his vocal effort grows, his right leg trembling in tandem with a watertight rhythm section.

“There’s a beautiful energy in here”, says Jagari, and he’s right. The room brims with bodies; shimmers with movement, with dancing relegated to a good-natured jostling between the shoulders of friends and strangers. All sense of ego seems to have been lost, soaked up by the permeating fuzz, like sound into a pillow.

The band set the tone when they play xylophone-heavy ‘Waile’, written decades ago by keyboard player Patrick Mwondela but heard recorded for the first time on Zango. Here, accompanying vocalists Theresa Ng’ambi and Hanna Tembo begin to shine, providing full-bodied, wailing harmonies to complement Jagari’s nostalgic lament. Jagari gives his contemporaries ample space to awe, frequently moving aside to bring their prowess to the anterior. He is careful to apply credit where it is due, and later even retires for two songs to eat an apple side-stage as they drive the charge.

This same ethos is applied to the rest of the company. During ‘Introduction’, Chanda takes pains to introduce every member of the band by name, repeating the mantra, “I love you… I need you” as each of them plays a short solo. The old hands are keen to showcase the aptitude of their younger collaborators, expressing a palpable gratitude for their alliance. Any sense of white saviourism one might have gained from the circumstances of their return is negated by the authentic joy pouring off the stage.

As the performance progresses it becomes more dynamic, the band feeding hungrily from the elation of the crowd. They hit their stride in a flood of undulating grooves, flitting easily between frantic proto-metal breakdowns and soulful, psychedelic refrains. Jagari twists and gyrates, gesturing ferociously, conducting a disordered dialogue of bodies and voices. He is athletic, charismatic; every bit the Jagger he is named after. Between songs, he and Mwondela share brief anecdotes and divulge the mythology surrounding some of the music.

For their final trick, W.I.T.C.H. are charmed back onto the stage for a heroic two-song

encore. They close the set with a prolonged and improvised version of James Brown’s ‘I Feel Alright’, joined on-stage both by support band Holiday Ghosts and much of the audience. The stage becomes a vortex of swinging hips and percussion. Punters score discarded drumsticks with which to beat glass bottles. Microphones are dispersed so that everyone can affix their voice to the coda. The enchantment extends almost until midnight, before concluding with a messy flourish.

The emphasis this evening is on story and history, from personal anecdote to the ancestral weight attached to numbers such as spaced-out ‘Malango’. There is a consciousness of the significance of cultural identity and oral tradition. Zango, Jagari tells us, means “meeting place”. In Zambian villages it is a place of learning, of teaching, of converging and welcoming. Tonight, we are privileged to be welcomed into a rich tradition of storytelling through the unyielding channel of song.