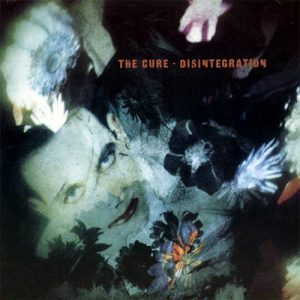

By the late 1980s, The Cure were in a pretty enviable position. They were playing huge sell out gigs on both sides of the Atlantic and successive albums were selling more and more. They were just as likely- or at least frontman Robert Smith was – to make it onto the cover of teen favourite Smash Hits as the inkies (as the likes of NME, Melody Maker and Sounds were known). While many acts who had come through the post-punk era had faded away, The Cure had grown stronger and stronger, challenging the notion of whether they might still be a ‘cult’ band.

So what was probably not expected was that they would return to the introspective gothic sound of the early 1980s. Surely that would be commercial suicide? As ‘alternative’ music became ever more marketable, there must have been those hoping that they would deliver something that would be marketable to the masses and see them playing the biggest venues yet.

There are, of course, differences between what marketing folk in suits think is a good idea and what’s actually happening within a band and the members. The band would end up playing ever bigger venues but not with an album full of upbeat pop numbers.

After considerable turbulence with line-ups some years previously, the band’s line-up had stabilised. The same line-up of Smith (guitars and vocals), bassist Simon Gallup, drummer Boris Williams, guitarist Pearl Thompson and keyboardist Lol Tolhurst had recorded both 1985’s The Head On The Door and 1987’s Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me. Keyboardist Roger O’Donnell (who had previously played with the Psychedelic Furs) was bought on board for the 1987 tour, and appeared in the video for the single ‘Just Like Heaven.’ Whilst Tolhurst had been in the band from the very beginning, he was battling alcoholism and was increasingly at odds with the rest of the band.

Robert Smith was also having his own difficulties. Whilst he acknowledges in the sleeve notes to the re-issue of the album that it was a good time to be in the band, he was increasingly worried about the thought that he would be thirty in 1989. It would have been almost understandable if the band had called their eighth album Fear Of Thirty. Whilst the Cure have never been the type to be that blatant with their lyrics (if we ignore the early John Peel session track ‘Desperate Journalist In Ongoing Meaningful Review Situation’), there are several sources that have suggested that Smith was battling depression around this time, worried that, by this age, most musicians have released their masterpiece.

If he knew then what we all know now, he really needn’t have worried. They just had to get it made.

While the lyrics are all attributed to Smith, this is very much a band record. While it is of a similar aesthetic to the earlier more gothic records like Faith and Pornography, it is not simply a re-tread of those records. The band met in 1988 to play each other pieces that they had been working on in the summer of 1988, and assembled early demos for the album at Boris Williams’ house in Devon. Here they demoed 32 songs, of which 12 would make it onto the final album. They then moved to Hookend in Oxfordshire, where on the first night a fire broke out in Robert Smith’s room and he battled flames to retrieve his satchel which had the lyrics in (there were reportedly no other copies available). While Smith has revealed that he lived like a mink in seclusion at points making this record, Roger O’Donnell has revealed more of a party atmosphere amongst the rest of the band.

The album opens with ‘Plainsong.’ This epic opener takes its name with the plain chant that has been used in religious ceremonies for centuries and the melody line does indeed sound like it could be a piece of church music (and I most definitely mean that as a compliment). Interestingly, my eleven year old son recently pointed out that he could see the similarity in this track and Joy Division‘s ‘Atmosphere.’ This is as much to do with the staggeringly beautiful keyboard lines played by Roger O’Donnell, who makes his presence felt on this album in the most amazing way. Having seen the band live on at least ten occasions, this is a track that they frequently open concerts with decades later. For those who haven’t had the privilege of seeing the band live, watching an audience stand up en masse as they begin to to play this piece really is akin to a religious experience. Whilst the Cure’s music has been used in films, this is a sign that had they wishes to go down the path of specifically composing soundtracks they would have carried it off with aplomb. Interestingly Mogwai – who have always been open about how much of an interest The Cure have been on them – have gone on to do a number of soundtracks.

[embedded content]

‘Pictures Of You‘ would become the album’s third hit single in the UK, albeit much edited down from the seven minutes. Reportedly influenced by the fire, on investigating his charred room, Smith found photos of Mary Poole and realised that these were far more important to him than the band’s lyrics.

[embedded content]

Even the greatest artists are prone to self-doubt and ‘Closedown‘ sees Smith listing his perceived shortcomings – ‘I’m running out of time, I’m out of step and closing down‘ he laments. He would return to similar themes on ’39’ on Bloodflowers, released eleven years later. As to whether he really suffered from self-doubt or whether he was self-editing what he released into the public domain, or a mixture of both, we may never be certain.

‘On Lovesong’ (also sometimes written as ‘Love Song’ – there’s no definitive spelling agreed up on it) was written as a wedding present to Robert Smith’s fiancée Mary Poole (they’re still married thirty-five years later). It ended up reaching no.2 in the Billboard Hot 100, the highest the band ever reached. Perhaps surprisingly the band were not that keen on it – though Smith told one interviewer that on hearing the song Mary had covered him with kisses. Amongst the covers of this song that have been done, Adele covered it on more of a ballad arrangement on her massive-selling 21 album in 2011.

[embedded content]

‘Last Dance‘, as with ‘Homesick‘ was originally only on cassette and CD versions of the album (latter re-issues from the twenty-first century have seen the album expanded to a two-disc set on vinyl). Another heartbreaking track, this deals with a childhood love that does not survive into adulthood -‘a woman now standing, where once there was only a girl.‘

For those who saw the Cure as po-faced (and who presumably had never listened to them properly – FOOLS! -‘Lullaby‘ is a wonderful exercise in dark humour. Influenced by the bedtime stories his father would read to him as a child, the song envisages Smith being eaten by a spider. Other theories – including video director Tim Pope – suggest that it’s an allegory for drug use or abuse. Children’s nursery rhymes can be a source of real darkness – once you get away from the sanitised Ladybird versions – and this is a hugely effective song. Perhaps surprisingly this song with it’s unforgettable video which won the band their first BRIT award reached no.5 in the UK singles charts; higher than even ‘Lovecats‘ or ‘Friday I’m In Love.’

[embedded content]

Simon Gallup’s extended bass line intro to ‘Fascination Street‘ is classic Gallup, taking his melodic bassline’s as the structure for another atmospheric Cure song, and parallels could be drawn with ‘Sinking‘ or ‘Screw‘ from The Head On The Door. The song is reportedly about Smith getting ready to visit Bourbon Street in New Orleans, and realising he was not actually sure what he was expecting to find.

[embedded content]

While it’s much less of a heavy-going album than Pornography, the second half of the album is far darker than the first. ‘Prayers For Rain’ takes the rain as a metaphor for cleansing or absolution and release. ‘The Same Deep Water As You‘ deals with an intense relationship, possibly as an allegory for mutual suicide, or that the relationship will ultimately be destructive of the individuals concerned. The title track is perhaps the only song that could have appeared on Pornography, and again it could be the narrator that is falling apart or another intense relationship -‘I never said I would stay to the end‘.’ Smith has often given many different answers when questioned on meanings of his work, it’s just there are so many layers lyrically as well as musically that a face value appreciation does not do it justice. It’s quite possibly Boris Williams’ finest track on the album.

‘Homesick‘ nods to Pornography‘s title track as it sees the urge to finish things and yet seek resolution or absolution.’ Homesick‘ is also reportedly the only track that Tolhurst contributed to. The flute sample on the track is his contribution – on the album sleevenotes he is credited as ‘other instruments.’ He left before the album was released in the spring of 1989.

‘Untitled‘ could almost have been called ‘Regret‘ with some of Smith’s most heartfelt lyrics ever, signing off the album with ‘I’ll never lose this pain/never dream of you again.’ The album fades away in a loop played on a harmonium (or something sounding very close to it), thus providing the perfect bookend to the album.

It may be a bleak album in places but it’s beautiful and one that this listener has never tired of hearing. As for its legacy, it seems pretty well assured. Yes, there were a number of era-defining records released in 1989, but for me and many others this goes well beyond the (admittedly pretty good) debuts from the likes of De La Soul, Soul II Soul or the Stone Roses, or albums from the likes of the more established Kate Bush, Bob Dylan or Neil Young. It’s an album – and indeed an era – that seems to be full of contradictions. A long, dark album that gave the band their biggest singles chart successes in both the UK and the US. Concern about existence that is ultimately life-affirming. Justification to Robert Smith that he was going to produce his masterpiece before he reached thirty. Many Cure fans – not just this one – consider this to be the band’s crowning achievement. It has become regarded as the second part of a trilogy of The Cure’s albums that start with Pornography and concludes with Bloodflowers. The Cure can do uplifting but they do dark despair so very well.

…and I know someone will bring this up, so I left this to the very final paragraph, A decade after the album’s release, Robert Smith appeared as himself in the South Park episode ‘Mecha-Streisand.’ Having defeated the foe, as Smith walks off into the sunset, cheered by the townsfolk, Kyle Brofloski yells out: ‘ Disintegration is the greatest album ever!’ He may very well be right.